We want to express our sincere appreciation to Dr. Lynne Anderson for her research and writing regarding this fascinating collection of Spanish samplers. This essay will become a significant reference source for collectors, curators and needleworkers.

These 12 samplers are from a private collection and each is available for sale as part of our Current Selections.

Samplers from Spain: An Introduction

Like most European countries, the history of sampler making by young girls in Spain spans a number of centuries and was influenced by a variety of factors. Samplers, usually referred to as “dechados” in Spanish, were frequently mentioned in the inventories of elite Spanish women, and passed to friends or family members at the time of their deaths. The word dechado has been used to denote embroidered pieces of cloth in Spain since at least the 15th century, where it appeared in a Latin-Spanish dictionary published in Salamanca in 1495. Another early (and often repeated) example is the inventory of more than fifty dechados owned by Queen Juana I of Castile (1479-1555), daughter of Isabella and Ferdinand, Queen and King of Spain (see figure right). In 1509 Don Juan Manrique de Lara, chief accountant to the Spanish royal family, made a descriptive list of the 26-year-old Juana’s moveable goods and recorded fifty-six dechados (some embroidered in silk or gold threads, some of drawnwork); twenty-five additional embroidered strips of fabric; and sixty-one “muestricicas,” a word used to denote very small dechados. From the descriptions it is clear that Queen Juana embraced a wide variety of motifs as her samplers were reported to include religious figures, as well as embroidered plants and animals, both real and imaginary.

Joanna of Castile, portrait by the Master of Affligem, c. 1500

Most Spanish girls and young women of the 18th and 19th centuries probably embroidered only one or two dechados. In her book Bordados Populares Españoles Maravillas Segura Lacomba suggests that Spanish samplers can be divided into two major types. The first she calls “dechados muestrarios” by which she means samplers that are primarily designed as practice pieces – samplers that enable a girl to demonstrate competence in the stitches or techniques being taught. These dechados may later serve as references for the sampler maker but are generally not meant to be displayed. The second type she labels “dechados magistrales” by which she means samplers that are masterful examples of girlhood needlework, each designed to be a finished piece representative of a specific sampler style or format. There are subgroups within each type, based on the sampler’s physical characteristics and what the sampler maker included (e.g., whether or not the sampler has a name, alphabet, or a date, etc.) but that is more detail than needed here. Given the importance of needlework in the education of young girls in Spain, it is likely that some Spanish girls made one or more “dechado muestrario” before tackling a more complicated and more sophisticated “dechado magistrale.”

The purpose of this essay is to provide an overview of Spanish samplers in general while also introducing the twelve Spanish samplers newly available for purchase at M. Finkel & Daughter here. All twelve samplers come from the same collection and represent an excellent opportunity to see a range of sampler styles and techniques popular in Spain during the 18th and 19th centuries. As is the case in other countries, Spanish samplers evolved in appearance over time, were influenced by regional preferences, and reflect both teacher expectations and students’ growing competence with a needle. Of the twelve samplers in this collection, the earliest were made in the mid-to-late 18th century. One is dated 1743, and two others can be attributed to the late 18th century based on similar known examples that include dates. Of the remaining nine samplers, five were made before 1830, three were made in the 1830s, and one, although undated, is probably a bit later. All the samplers would be classified as “dechados magistrales” – formal examples of Spanish girlhood embroidery designed to be displayed.

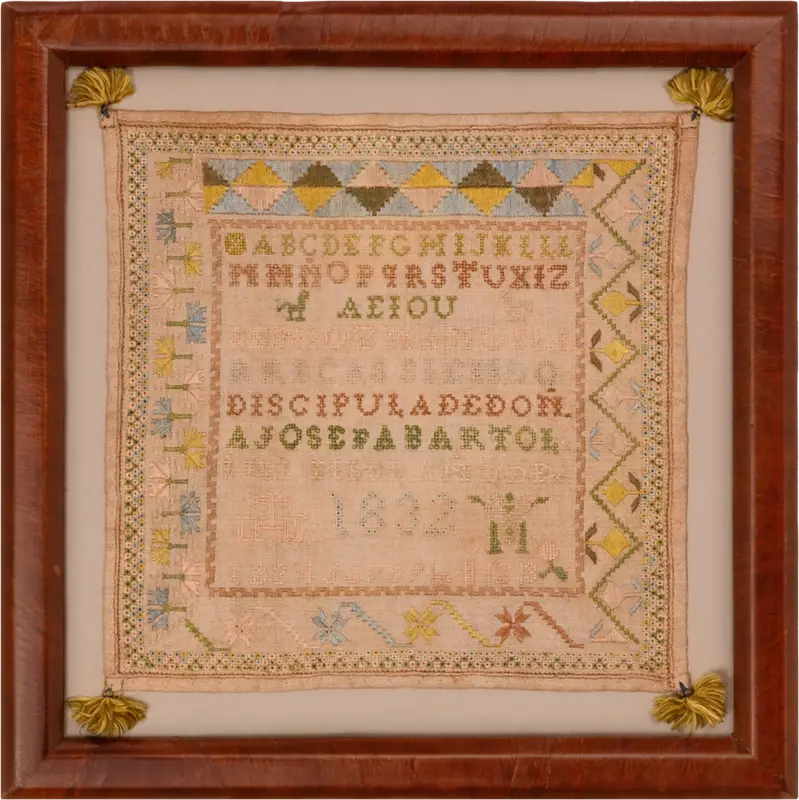

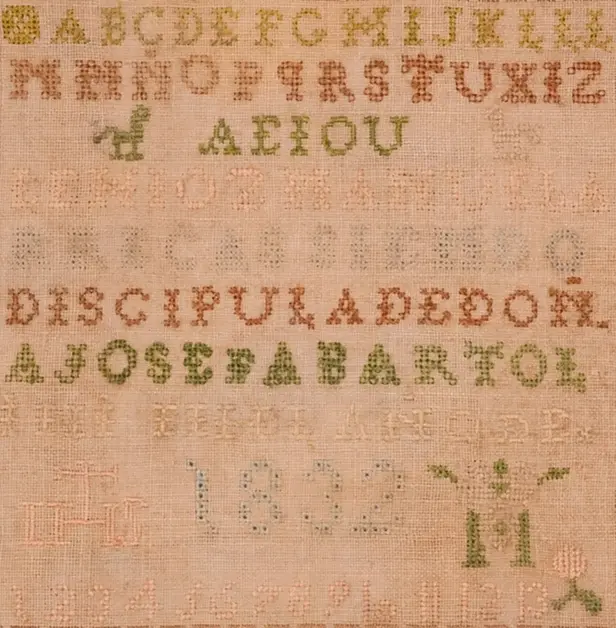

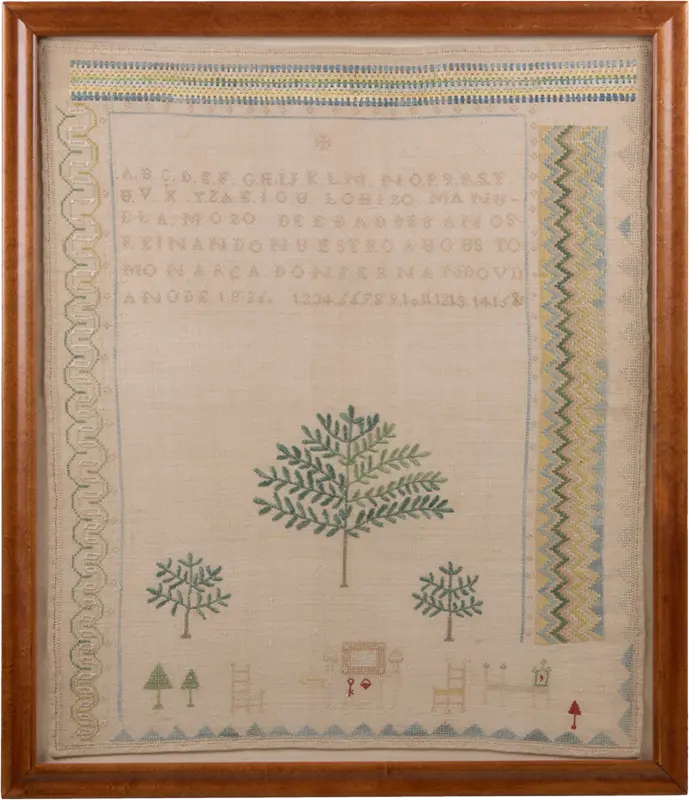

One example is the small but well designed and carefully executed 1832 sampler by Manuela R. Recas (see figure 1). In the center she demonstrated her competence with the Spanish alphabet, the Spanish vowels of AEIO and U, and then a signature in which she recorded her name, the name of her teacher, and the year: “Le hioz Manuela R. Recas siendo discipula de Doña Josefa Bartolini en el año de 1832.” (See figure 1.1) A translation reads:

"Made by Manuela R. Recas while a disciple (student) of Doña Josefa Bartolini in the year of 1832.”

Figure 1. Spanish sampler made by Manuela R. Recas in 1832 under the instruction of Doña Josefa Bartolini.

Figure 1.1. Detail of Manuela R. Recas sampler inscription.

Interestingly, even though this sampler was clearly made to be displayed, her first two words are incorrectly spelled. They should read “Lo hizo” not “Le hioz.” Manuela’s signature is followed by the letters IHS, a Latin monogram for the name Jesus, originally formed from the first three letters of his name in Greek. At the bottom are the numbers one to thirteen. Surrounding this central rectangle of text are four carefully balanced decorative bands, each displaying a different repeat design of floral or geometric motifs, revealing Manuela’s skill with satin stitch. Enclosing all is a four-sided border of three rows of eyelet stitch.

The finishing touch, and the key to knowing this sampler is a “dechado magistrale” designed for display, are the four tassels, one on each corner. Spanish samplers are frequently adorned with tassels and fringes along the perimeter of the needlework, decorative elements adopted from another culture but incorporated into Spanish embroidery as essential. Mildred Stapley in her 1924 book entitled Popular Weaving and Embroidery in Spain explained:

“Spain, true to its oriental heritage, remained a land of fringes and tassels… Without a tassel at each corner at least, a table-center, pillow-case, or bedspread would hardly have been considered complete” (p. 23).

To this list we can add Spanish dechados. Girls in Spain were clearly being taught the importance of adding this finishing touch by incorporating the same onto their girlhood embroideries.

In the following sections, this essay provides a brief look at the importance and role of embroidery in a Spanish girl’s education, followed by a discussion of various features found on Spanish dechados, illustrated with images from the twelve samplers accompanying this introduction.

History

Learning to sew and to embroider were essential elements in a Spanish girl’s education up to and including the early 20th century. In a 2000 publication discussing samplers in the collection of the Hispanic Society of America, Del Álamo Martínez wrote that “the education of a girl was considered complete in rural Spain in the 19th century when she knew the catechism, the rules of basic arithmetic, something of geography, and the stitches, which meant that she was prepared to make a sampler.” Education for most girls in 18th and 19th century Spain was focused on preparation for the domestic sphere and there was little emphasis on teaching girls to read and write. As late as 1860, less than 12% of the women in Spain were literate (as compared to more than 40% of the men), leading to one of the lowest literacy rates in all of western Europe. Even girls who attended school often never achieved a full grasp of the skills needed for independent reading and writing, usually due to low expectations and poor instruction.

Figure 2. Spanish sampler made by 12-year-old Juana Dominguez in 1743 while a student of Doña Antonia Fernandez.

Although making a sampler may have been seen as a culminating activity in a Spanish girl’s needlework education, it was also assumed that a girl’s sewing and embroidery expertise would be put to use at home. In addition to the making and mending of household textiles, each girl was expected to sew and decorate linens for her trousseau, ornament the clothing she wore on festive occasions, and eventually make a wedding shirt for her “novio.” Girls from the wealthy families of Spain pursued a course of needlework instruction similar to those in the poorer, more rural areas of the country, but their dechados reveal some significant differences. For elite girls living in or near urban areas, embroidery materials were usually of higher quality, instruction was often more demanding, and education might last longer due to more available opportunities – leading to advanced instruction and dechados that are more complex and show greater dexterity with the needle.

Scholars of Spanish embroidery cite the need to know a bit about the history of Spain to appreciate the cultural influences reflected in Spanish women’s embroidery. Most important is the fact that the Iberian peninsula, the geographic location of both Spain and Portugal, was invaded and occupied by the Moors of North Africa in the 8th century, establishing an Islamic civilization that flourished for centuries and affected all aspects of Spanish culture including language, science, agriculture, architecture, food, medicine, music, and of course the decorative arts. For approximately 700 years, followers of the three major religions in Spain (Islam, Christianity, and Judaism) coexisted in a relatively tolerant environment, allowing for artistic cross-cultural adoption and adaptation. This changed in the 15th century when Christian armies, after centuries of effort known as the “Reconquista,” were finally successful in defeating the Moors, culminating in the fall of Granda in 1492 and the establishment of Isabella and Ferdinand as the “Catholic Monarchs” of a united Spain. Many Moors remained in Spain, and although forced to convert to Christianity, they continued to have a profound influence on Spanish culture. It wasn’t until the beginning of the 17th century that the remaining “Moriscos,” many of whom were craftsmen and merchants, were forcibly expelled from the country, resulting in a religiously unified Spain.

Collectors and scholars of Spanish dechados point to a number of features they feel reflect Moorish influence. Top of the list is a penchant for repetitive geometric designs, many of which are quite complex and embody high levels of mathematical precision. A great example of this is the sampler made by twelve-year-old Juana Dominguez in 1743, which is also the oldest sampler in this group (see figure 2). Her teacher, Doña Antonia Fernandez, was clearly a highly skilled needleworker and had high expectations for her students. Like many Spanish samplers Juana’s needlework is constructed around a central square, in this case filled with a finely stitched rural scene of a young girl near a pond leading a bull and a flock of sheep under huge clouds (see figure 2.1).

The majority of the sampler, however, is composed of concentric decorative bands of different geometric patterns comprised of polygons within polygons – triangles, squares, rectangles, hexagons, and octagons – many with stylized floral motifs in the center also constructed from polygons (see figure 2.2). These highly detailed and beautifully intricate patterns reflect the architecture and decorative preferences of the Moors, and were widely adopted by Spanish women for their embroidery, especially in the southern and western parts of the country. Around the outside edge Juana added a delicate fringe of looped threads and tiny tassels, revealing yet another decorative influence from Moorish northern Africa.

Figure 2.1. Detail of Juana Dominguez sampler.

Figure 2.2. Detail of Juana Dominguez sampler.

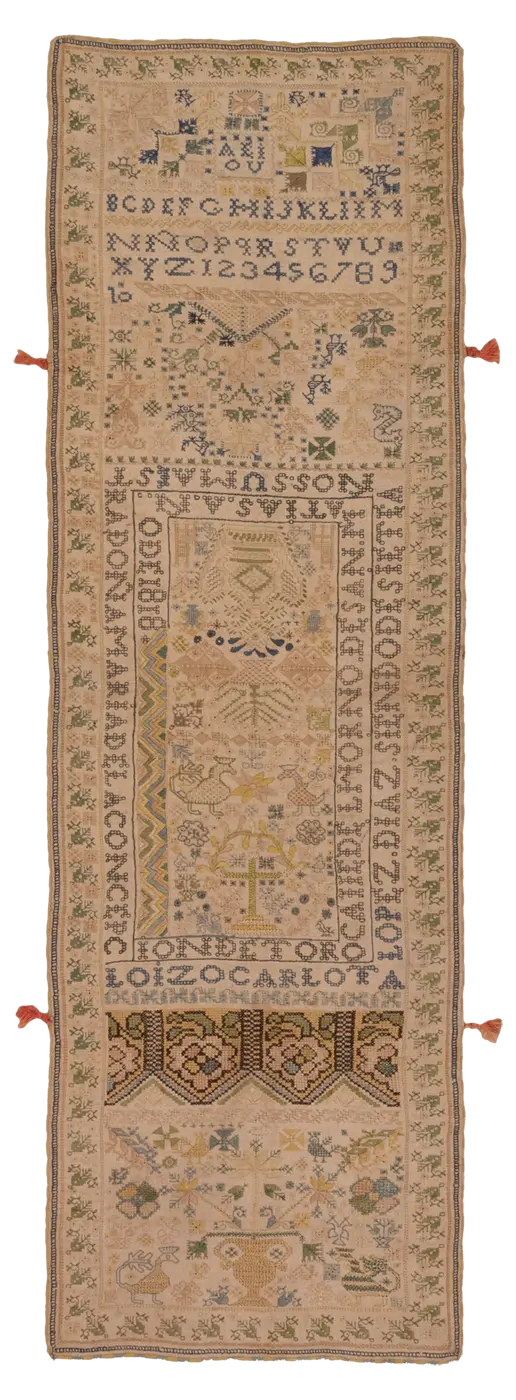

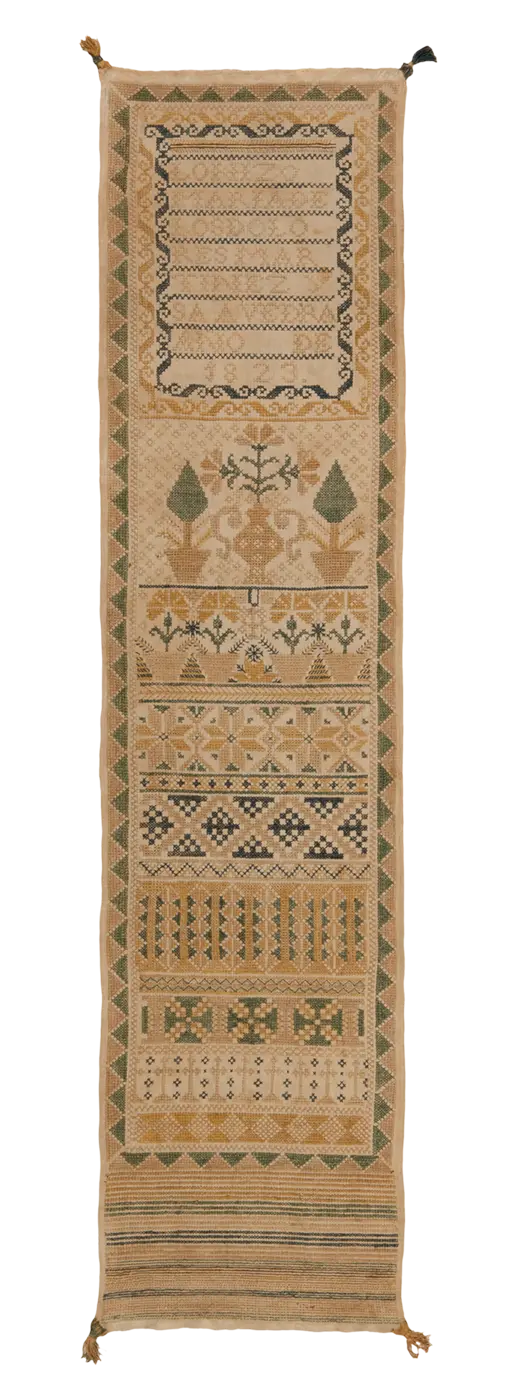

The shape and format of Spanish samplers have, of course, evolved over time. The oldest known samplers were made from long panels of homespun linen, with decorative bands and motifs that stretched across the short length of the fabric. Beginning in the middle of the 18th century, a square format came into popularity, such as the one made by Juana Dominguez in 1743 (see figure 2), but long rectangular samplers were still made. Below are two 19th century examples of the long format sampler from this group. The first was made by Carlota López Diaz in 1818 (see figure 3) and is 29.5 inches long. The second was made by Maria de los Dolores Martinez in 1823 (see figure 4) and is 39 inches long. Although completed only five years apart, their striking differences reflect regional preferences as well as ties to different embroidery traditions.

Figure 3. Spanish sampler made by Carlota López Diaz in 1818 under the instruction of Doña María de la Concepción de Toro on the “Calle del Horno de San Matías” in Grenada, Spain.

Figure 4. Spanish sampler made by

Maria de los Dolores Martinez in 1823.

Motifs

The artistic appeal for both of these long samplers relies heavily on the motifs their makers decided (or were instructed) to include. According to Segura Lacomba there are five types of motifs found on Spanish samplers, with preferences varying by region and time period. The types are (1) anthropomorphic motifs (representations of all or part of the human figure); (2) zoomorphic motifs (representations of animals, either real or imaginary); (3) phytomorphic motifs (representations of plants, either realistic or stylized); (4) symbolic motifs (representations of objects that hold symbolic meaning, usually religious); and (5) geometric motifs (designs made with lines and shapes, both straight and curved). Many motifs fit into more than one category. For example, the rose motif is both phytomorphic (representation of a plant) and symbolic (usually interpreted as a symbol for love). The symbolic nature of a motif can also mean different things to different groups of people. For example, the motif of a pelican pecking at its breast to draw forth blood for its young can be interpreted as a sign of maternal love and sacrifice. In the context of Christian Spain, this motif is also symbolic of sacrifice, but that of Jesus Christ sharing his blood and flesh in the Eucharist, or Holy Communion.

The 1818 sampler made by Carlota López Diaz is designed to highlight the many diverse motifs she embroidered in her three central panels: upper, middle, and lower. In the bottom part of the middle panel, for example (see figure 3.1), Carlota embroidered a large number of floral motifs, some in baskets and some floating unconstrained on the fabric, as well as some pretty impressive birds with long tails and crowns. We believe the birds are meant to represent peacocks, a sacred bird in many religions and a symbol of eternal life in the Christian faith. Prominent is a large cross, symbolic of the crucifixion, with a colorful garland across the top. Central to the lower panel (see figure 3.2) is a large vase with stylized flowers, flanked with two more renditions of the large bird with long tail and crown.

Figure 3.1. Detail of the 1818 Spanish sampler by Carlota López Diaz showing diverse motifs in the sampler’s middle panel.

Figure 3.2. Detail of the 1818 Spanish sampler by Carlota López Diaz showing diverse motifs in the sampler’s lower panel.

The 1823 sampler made by Maria de los Dolores Martinez is also a showcase for motifs but in a more restrained and organized way. Below her nicely framed signature are wide decorative bands within which Maria embroidered stylized representations of floral motifs and geometric patterns. In the top band (see figure 3.3) Maria stitched a large decorated vase with flowers flanked by two evergreen trees in pots. By embroidering a background full of “stars” Maria gave the fabric a stippled, three-dimensional effect, also a popular decorative technique borrowed from the Moors. The decorative band below displays a row of stylized carnations, the most frequently represented flower on Spanish samplers, also symbolic of love. In Maria’s carefully constructed sampler, both floral and geometric motifs are center stage but at the same time neatly constrained within the horizontal bands enclosed with her sawtooth border.

Figure 4.1. Detail of the 1823 Spanish sampler by Maria de los Delores Martinez showing two bands of plant motifs.

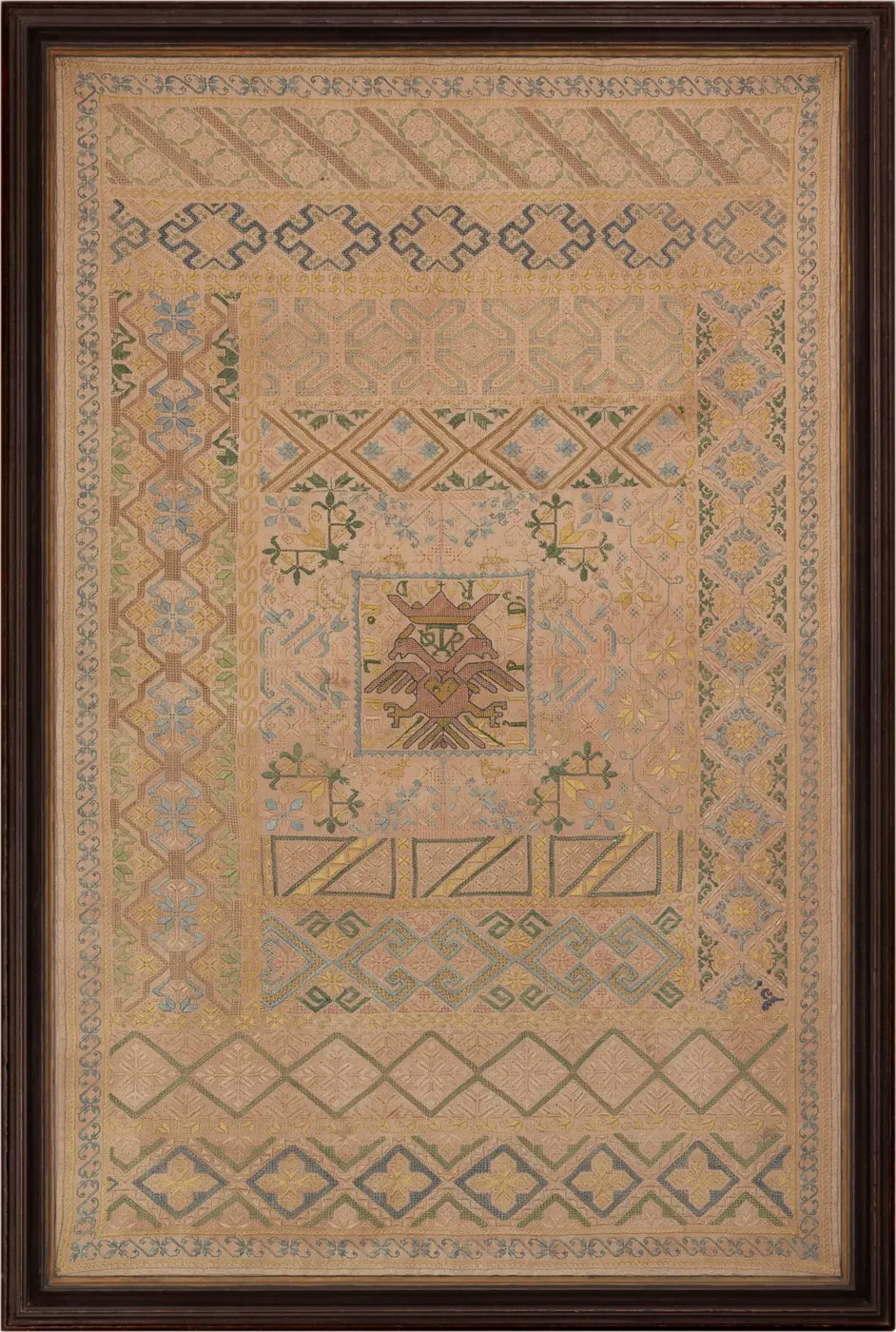

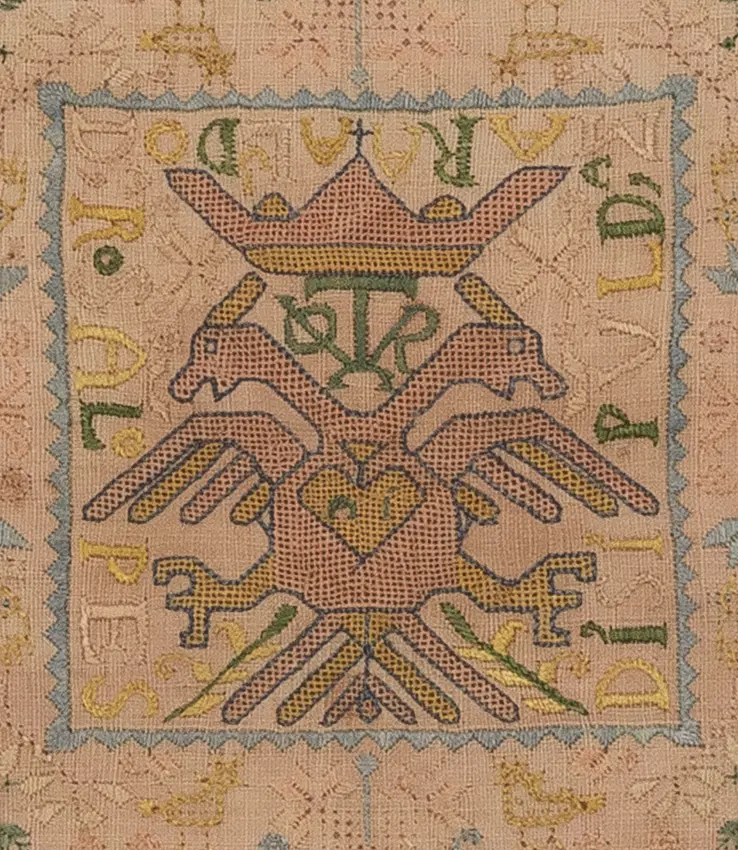

Sometimes a single striking motif can be the essential key to revealing unknown information about a sampler – and this is true with Spanish samplers as well. Two of the dechados in this group include a large central motif of a two-headed eagle with an ornate crown, both of which are undated. Known today as the “Hapsburg eagle” this ancient symbol was adopted during the reign of the 16th century Spanish king Charles V to symbolize the union of the Hapsburg dynasty with the Spanish monarchy. Maria Juliana Blazquez’s version of this important motif sits in the middle of concentric decorative bands with geometric motifs that have more than a hint of Moorish influence (see figure 5). A four-sided border of stylized carnations, stitched on the diagonal, surrounds the whole.

Figure 5. Spanish sampler with the “Hapsburg eagle” as a central motif. It was embroidered by Maria Juliana Blazquez in the late 18th century.

Spanish samplers with the same central motif, found in museum collections and publications on Spanish embroidery, suggest that Maria Juliana Blazquez embroidered her sampler sometime in the late 18th century. A sampler illustrated and discussed by Stapley has an identical central motif surrounded by similar concentric decorative bands of geometric designs, and also has an outside border of stylized carnations embroidered on the diagonal. The sampler was made in Toledo, Spain by Bernabela Gonzalez in 1771. In her book on Spanish embroidery Segura Lacomba illustrates and discusses three similar samplers with a central motif of a double headed eagle sporting an elaborate crown, one of which is dated 1789. The example most resembling the work of Maria Juliana Blazquez is described by Segura Lacomba as having “venerable antiquity” and includes a similarly brief signature above the eagle’s crown, Maria Del Rio, with no date. With these and other similar Spanish samplers as comparisons, the evidence strongly supports a late 18th century attribution.

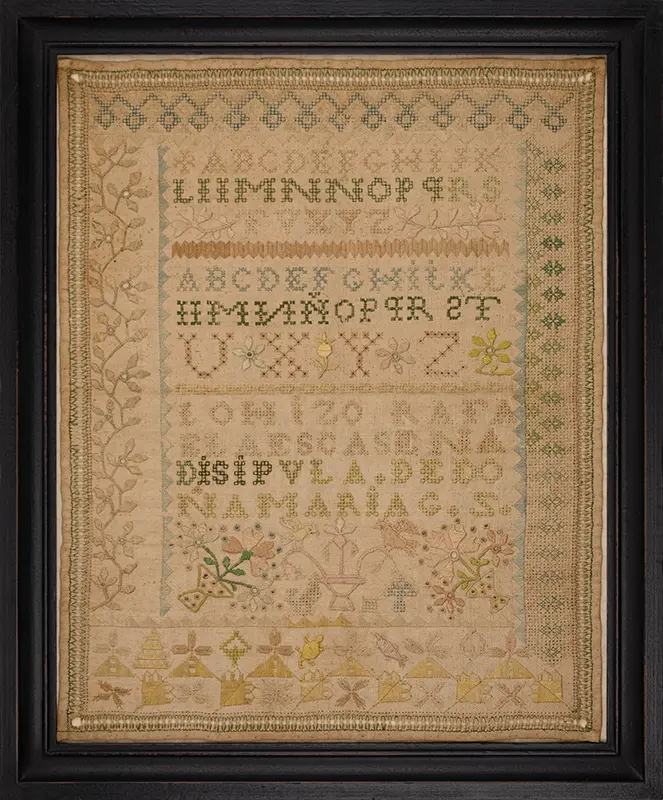

Another undated sampler in the group can be attributed to the mid 19th century based on its motifs. Throughout most of Spanish history, embroidered motifs were primarily geometrical in design, accompanied by stylized renditions of plants and animals. Toward the middle of the 19th century, foreign influences from neighboring European nations started to appear on Spanish women’s embroidery, including girlhood samplers, resulting in more realistic renditions of floral and animal motifs. On Rafaela Escasena’s undated sampler (see figure 6), for example, she embroidered a floral border on the left that is not traditional to Spanish embroidery. The meandering vine with leaves and flowers is less constrained and more realistic in appearance than the stylized versions usually found on Spanish samplers. The same is true for the two corner vases at the bottom, each with three embroidered flowers. These motifs suggest a foreign influence and therefore an attribution to the middle of the 19th century. And for fun, look carefully at the band across the bottom to see Rafaela’s rendition of both a turtle and a fish.

Text

Figure 6. Undated Spanish sampler by Rafaela Escasena showing foreign influence in design and motifs.

A high percentage of Spanish samplers include some type of text, but rarely the poetic verses and moral aphorisms found on English and American samplers. Sometimes the text is simply an alphabet or a name, but more often there is additional information revealing something about when and where the sampler was made or the teacher responsible for the girl’s needlework instruction. In this group of twelve Spanish dechados, all of the girls embroidered their names, and nine included the year in which they worked on their sampler. All but three of the girls began their signatures with the words “lo hizo” which is usually translated as “made by” or “made it.” Six of the girls stitched one or more alphabet and five of the six also stitched the five Spanish vowels: AEIOU

Although the modern Spanish alphabet has 27 letters, the alphabets copied by girls when embroidering a dechado usually had only 23 to 25 letters. In early Spanish orthography the sound made by the letter J was represented by the letter I (this was also true in English) and the sound of U was represented by the letter V. So, J and U may or may not appear in the girl’s stitched alphabet, depending on origins of the alphabet she used as a model. In addition, the letters K and W were not originally part of the Spanish alphabet, appearing only in words borrowed from other languages. K was accepted into the alphabet in the mid 18th century, but then rejected by the Royal Spanish Academy in 1815, only to be readmitted in 1869. The letter W almost never appears on a Spanish sampler as it was the last letter added to the Spanish alphabet, not formally adopted until 1969. Unique to the Spanish alphabet is the inclusion of two different Ns, the second one having an accent above it and pronounced “eñe.” On Spanish samplers, the Ñ appears in words like año and Doña. Some of the girls’ alphabets include an Ñ but others do not. In Spanish writing there are other letters that sometimes have accents, but they are not considered separate letters. In short, there is a lot of variety in the alphabets stitched on Spanish samplers.

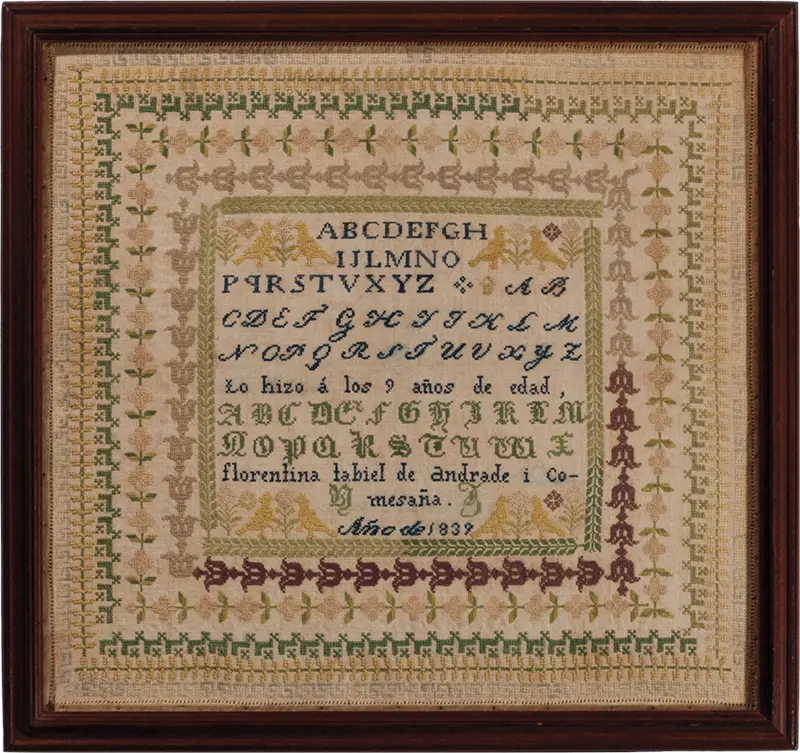

Figure 7. Spanish sampler with three alphabets, made by nine-year-old Florentina Tabiel de Andrade i Comesaña in 1839.

In 1839 nine-year-old Florentina Tabiel de Andrade i Comesaña embroidered a well-designed sampler made of graphically tight concentric bands composed of stylized floral motifs (see figure 7). The center is filled with three alphabets, all in capital letters but each in a different “font.” The first alphabet has 23 letters, including a J but missing the U and the K. The second alphabet has 25 letters and includes both a J, a U, and a K. The third alphabet has neither a J or U, but does have a K and a W. And none of the three alphabets include the Ñ. A look back at the undated sampler by Rafaela Escasena (see figure 6), however, reveals that she stitched two alphabets, both including the Ñ next to the non-accented N. From the five Spanish alphabets on just these two samplers there are four different versions, all correct at some point in the history of Spanish orthography.

In addition to her three alphabets, Florentina embroidered her full name – Florentina Tabiel de Andrade i Comesaña – recording in stitches the surnames of both her father (Tabiel de Andrade) and her mother (Comesaña). Spanish naming conventions are fairly complicated, and differ over time and across geographical boundaries, but it is helpful that women did not change their names upon marriage. So, when a Spanish sampler maker provides both surnames (usually connected with a “y” or an “i” meaning “and”) it is often possible to conduct a successful genealogical search. And this is the case with Florentina, who we learned was born in the year 1830 in Seville, the capital and largest city of Andalusia, in southern Spain. Her father, Francisco de Paula Taviel de Andrade y López, was an attorney from an elite family in Andalusia who also served as secretary to the Royal Court when it was in Seville. For his service to the monarchy Florentina’s father was awarded the “Caballero de la Orden de Carlos III,” a knighthood and one of three permanent orders of merit bestowed by the kingdom of Spain. Florentina’s mother was Andrea De Comesaña y Diaz Galindo, also from an elite Andalusian family. During Florentina’s childhood her family amassed a large amount of land where her father bred and raised cattle for the bull fighting ring. Florentina married Pedro de Porres y Castillo (1832–1889) and together they had at least six children.

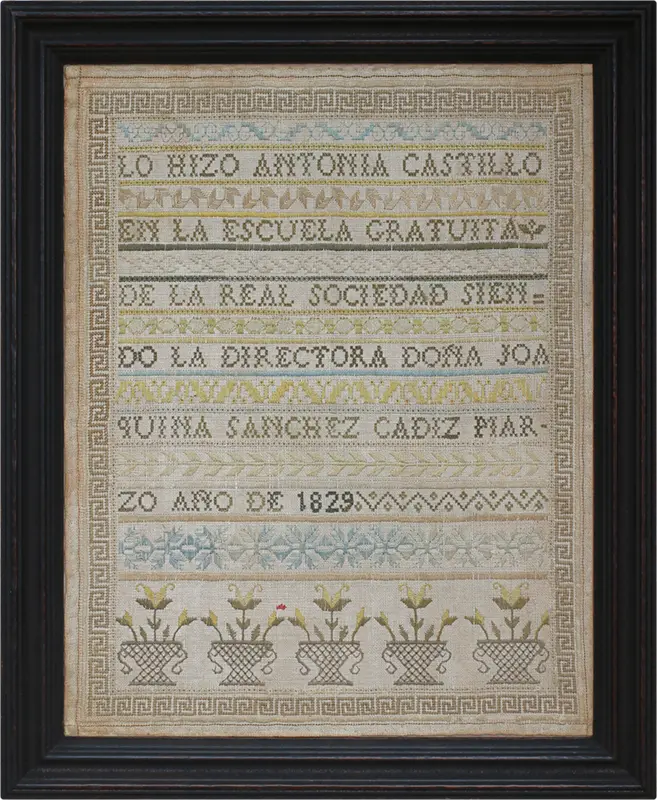

Figure 8. Spanish sampler made by Antonia Castillo of Cadiz, Spain in 1829. Her signature includes information about her school, its location, and the name of its director.

Most of the sampler makers in this group did not include the surnames for both parents, making identification difficult. Antonia Castillo, however, provided a wealth of information about her school: its name, its location, and the name of its director (see figure 8). A translated version of her signature reads:

Made by Antonia Castillo at the Free School of The Royal Society under the Director Doña Joaquina Sánchez, Cadiz, March Year of 1829.

From this we learn that Antonia was attending a free (public) school in Cadiz directed by Joaquina Sanchez and sponsored by the Royal Society. In the 19th century public schools were founded in Spain to extend educational opportunities to students from a broader range of economic strata and diminish the role of the Catholic Church in Spanish education. Working class girls at the Escuela Gratuita de Cádiz were taught basic rules of etiquette while also learning practical sewing techniques, followed by lessons in lacework and embroidery for those who excelled. The director of the school, Doña Joaquina Sánchez, was appointed by the Cádiz Ladies' Board on May 17, 1827 but dismissed by the same board in the summer of 1829, a few months after Antonia completed her sampler.

Although the name Antonia Castillo is not uncommon, the Municipal Records for Cadiz, 1784-1956 suggest there was only one girl with that name born in Cadiz about the right time to be creating a dechado in 1829. Daughter of Nicolás Castillo and Antonia Morales, this Antonia Castillo was born in the year 1819, which would have made her ten years old in 1829. On May 29, 1858 Antonia married Rafael Chacun, but died three years later on February 15, 1861 from enteritis. She was only forty-two years old.

Winner of the prize for the most information stitched on a Spanish dechado in this group goes to Serafina Escacena who signed and dated her densely embroidered sampler in 1836 (see figure 9). Integrated between Serafina’s multiple dividing lines and decorative bands are more than sixty words of text, recorded in different “fonts” that varied line by line, making some of it difficult to read. The first part of Serafina’s signature introduces herself, her teacher, and her school. Translated, it reads:

“Made by Doña Miss Serafina Escacena disciple of Doña Mrs. Ana Maria Villazon y Mazamoro in this Royal Academy for Young Ladies 17 of July in the year 1836.”

There are two important things to note about this signature. First, contrary to popular belief, the word Doña does not signify that a woman is married and so does not translate to Mrs. We have left the word in Spanish because there is no perfect translation into English. Doña is an honorific which signifies the bearer is of an elite social class, probably from a family of wealth but not necessarily. According to Dr. Mayela Flores Enriqués, foremost scholar of 19th century embroidery in Mexico, the word is best translated to the English honorific “Lady,” as in Lady Jane Grey, the Tudor monarch who reigned over England for a mere nine days. The word Doña was used by both married and unmarried women, and is the female equivalent to Don, as in Don Quixote. Evidence for this can be found in Serafina’s signature, where she uses the word Doña to refer to herself (who she also indicates is unmarried by calling herself “la señorita”) and to refer to her teacher (who she indicates is married by referring to her as “la señora”).

Figure 9. Spanish sampler by Doña Miss Serafina Escacena in 1836 at the “Real Academia de Señoritas Jóvenes” when a student of Doña Mrs. Ana Maria Villazon y Mazamoro.

The second important thing to note is the use of the word discípula (written here and often on other Spanish dechados as “disipula.”) The most literal translation is of course “disciple,” but in Spanish the word does not always connote someone who follows a religious leader or spiritual philosophy as it does in English. When embroidered on a girl’s sampler the word discípula simply indicates a female student who is receiving instruction from a respected teacher, whose name is also included. On samplers there are many ways girls could choose (or were assigned) to include the name of their teacher, in Spanish as well as English. Use of the word disciple, discípula, is extremely common on Spanish dechados, but very rare on those made in Mexico, and probably non-existent on samplers made in England or the United States.

The second part of Serafina’s signature was undoubtedly composed by her teacher, who presumably tasked Serafina with embroidering it on her dechado. Loosely translated it reads:

This work clearly demonstrates the skill of a girl I had the good fortune to direct. It is not difficult to infer the merit that lights up so limited a space.

It is extremely rare for a sampler to include a note from the maker’s teacher, much less a note that provides an evaluation of the girl’s needlework expertise.

Methods and Materials

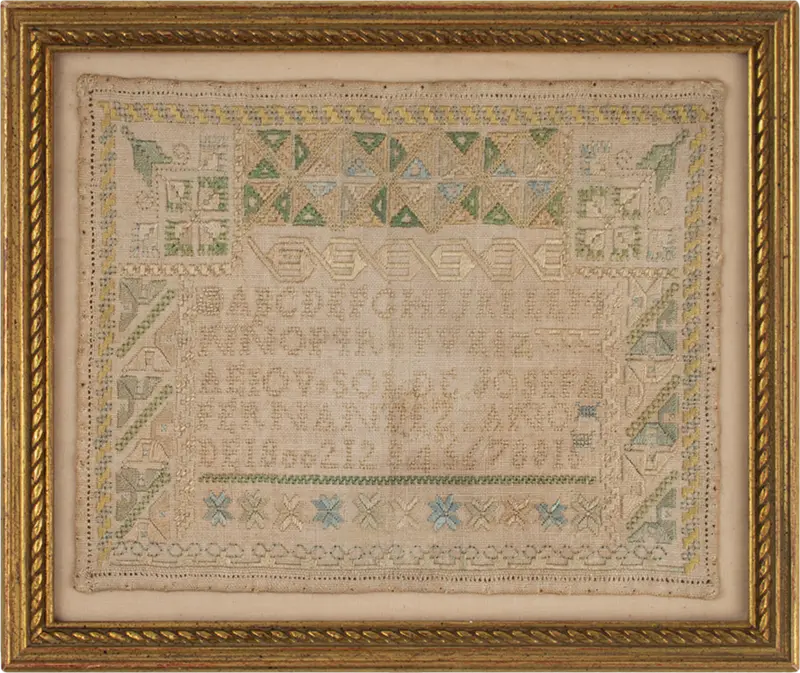

Figure 10. Miniature Spanish sampler made by Josefa Fernandez in 1800.

Spanish dechados can often be distinguished from samplers made in other Spanish speaking countries by examining their color combinations and dominant needlework techniques. In general, the colors of Spanish samplers are fairly subdued and there is more emphasis on “hilos contados” (counted threaded work) than on surface embroidery. In her book on Spanish needlework Stapley was careful to point out that women in different regions of Spain had preferences for different color combinations:

Spanish taste was first for black on white; bright colored embroidery took second place in their affections; and white, last. The province of Salamanca inclined most to black; blue was preferred in Galicia; red and yellow together, in Estremadura; while around Toledo and Avila, blue and golden brown were combined. Thus, we see that Spanish embroideries were for the most part sober.” (p. 35)

Some of these color preferences are apparent on the Spanish dechados in this collection. In 1800 Josefa Fernandez completed a miniature sampler that included a Spanish alphabet, five vowels, her name, the year she worked her sampler, and a series of numbers, all stitched using a tan colored thread (see figure 10). In Spanish this light tan color is referred to as “miel” in honor of its similarity to the color of “honey” and it is one of the most popular colors for Spanish dechados, often in combination with yellow, green, and light blue as seen on Josefa’s sampler. When a somewhat darker shade of tan is needed for contrast, the thread color is referred to as “canela” or cinnamon. Threads of this color can be seen on the sampler by Serafina Escacena (see figure 9).

Although the sampler is small in size, Josefa was able to demonstrate her skill with the three most common stitches to appear on Spanish dechados: cross stitch, back stitch, and satin stitch. The other stitches she used, for example long-arm cross and four-sided stitch, are variations on these three basic techniques. According to Stapley, there is a Spanish preference for graphically appealing repetitive designs rather than complex needlework stitches, resulting in samplers that “exhibit much more feeling for pattern than ingenuity for stitchery” (p. 31). Stapley explained the girls’ preference for counted stitch work by indicating that up until the middle of the 19th century dechados from most rural areas of Spain were embroidered primarily with linen or wool thread on a handspun and hand-woven linen ground, materials that lend themselves to stitches and techniques that rely on counting threads.

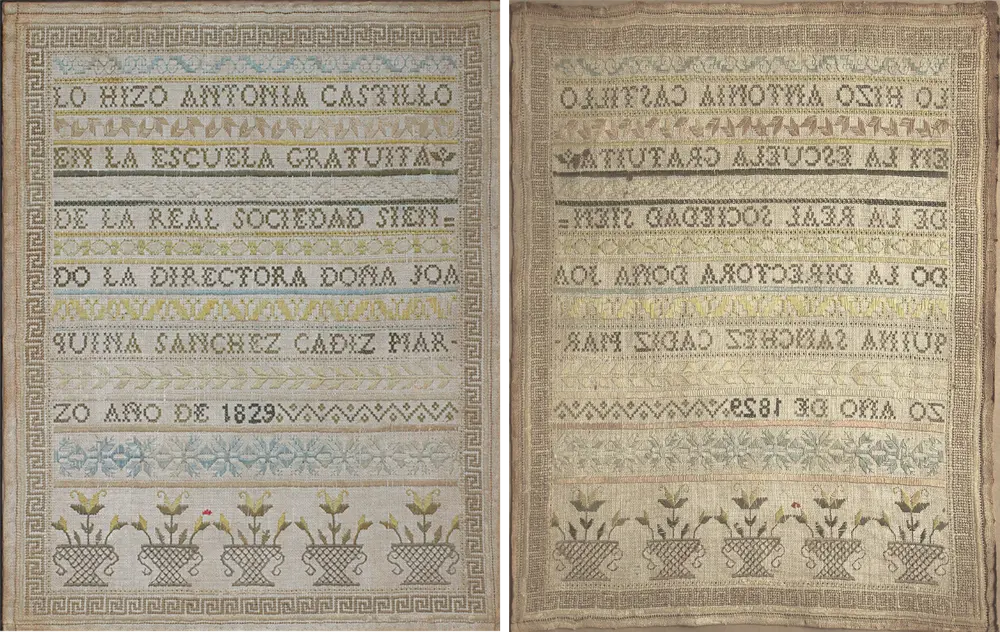

Figure 11. Front and back sides of an 1829 Spanish sampler by Antonia Castillo.

None of the above is meant to disparage the excellent craftsmanship displayed on Spanish samplers. One the easiest ways to appreciate the fine teaching and superb needlework is to look at the reverse side of a sampler. It is traditional in Spain for the needlework to be as exemplary on the back as it is on the front. For example, a comparison of the two sides of Antonia Castillo’s sampler (see figure 11) reveals the use of reversible stitches and needlework techniques that present a neatly embroidered, and even legible, reverse side.

Some Spanish samplers include decorative bands that stand in stark contrast to the lightly stitched designs based on intricate geometric shapes and repetitive floral motifs. Manuela Mozo’s 1826 unfinished sampler, for example, includes two densely stitched decorative bands that appear to be experiments with color, one across the top of her sampler and one down the right-hand side (see figure 12). Scholars of Spanish embroidery point to these repetitive designs of alternating colors as yet another testimony to the Moorish influence on Spanish embroidery. Similar bands using multiple types of filling stitches also appear at the top of the 1826 sampler by Manuela R. Recas (see figure 1); at both the top and bottom of the 1743 sampler by Juana Dominguez (see figure 2); and at the top of the 1800 sampler by Josefa Fernandez (see figure 10).

Figure 12. Spanish sampler made by eight-year-old Manuela Mozo “during the reign of our august monarch Don Fernando VII year of 1826.”

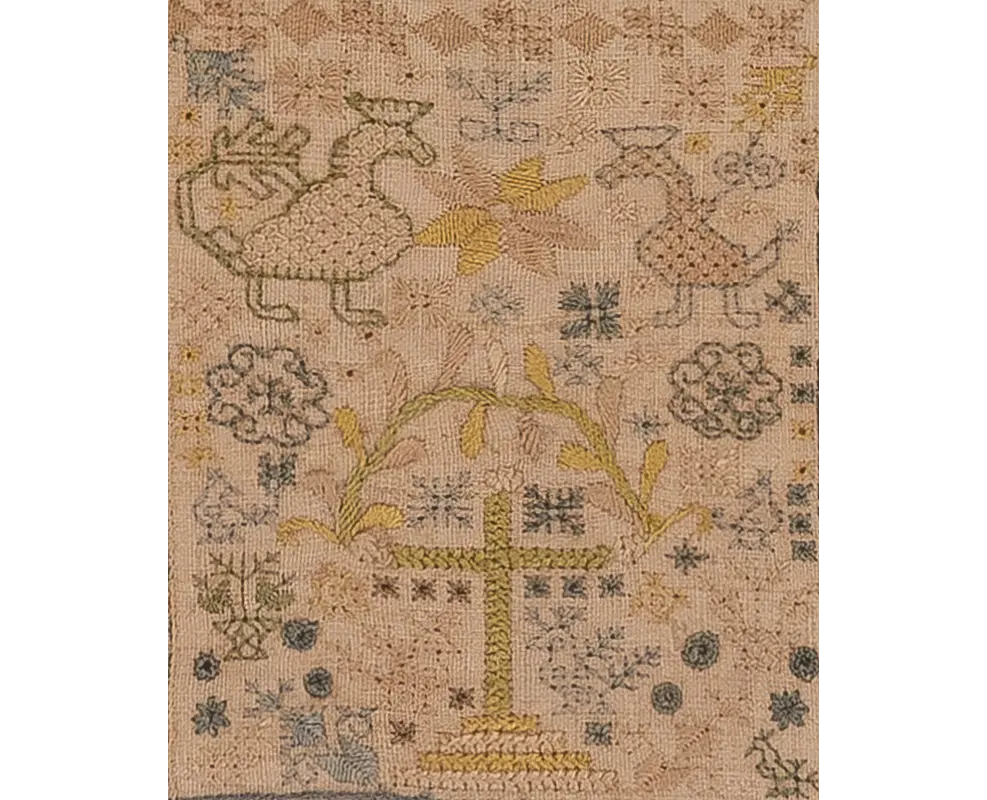

And of course, for every generalization one makes about samplers, there are always exceptions. The undated but magnificent sampler by Rosa Lópes is covered with brightly colored silk threads and would never be considered “sober” (see figure 13). Furthermore, it documents Rosa’s exceptional talent with the needle, including the use of stitches and techniques not displayed on other Spanish samplers in this group. Rosa’s sampler has all the expected hallmarks of an outstanding Spanish dechado: (a) intricate concentric bands based on repetitive geometric patterns and stylized floral motifs in graphically appealing designs; (b) a large, culturally important central motif of the double headed “Hapsburg eagle”; and (c) a signature circling that motif that records both her name and her position as the disipula of her teacher, Doña Mara Alvarado. In addition, however, are some unique features, best seen by examining specific details.

Figure 13.1, for example, is a detail of the central square on Rosa’s sampler and showcases a somewhat terrifying version of the Hapsburg eagle. Outlined in seed stitch, the eagle and crown are filled using a relatively simple drawnwork technique that required removing one or two threads at regular intervals and then wrapping the remaining threads with silk floss. This same technique was used in many of the concentric bands on Rosa’s sampler, as seen in figure 13.2. Although drawnwork only shows up occasionally on the Spanish samplers in this group (mostly as a hemstitch), various forms of this needlework practice were taught to Spanish girls and Spanish dechados comprised entirely of drawnwork exist. In Spanish the generic term for drawnwork is deshilado and the practice was so common that any collection of old linens might be referred to the “deshilados.”

Figure 13. 18th century Spanish sampler by Rosa Lópes, embroidered while a student of Doña Mara Alvarado.

According to Stapley, Spanish girls were also taught to increase the visual interest of animal and floral motifs done in satin stitch by altering the direction in which different sections were embroidered. In her words: “great diversity was obtained by laying off a certain area…into checkers, lozenges and chevrons and changing the direction of the stitch in each unit” (p. 31). A close examination of Rosa’s sampler shows that she was quite skilled in this technique, as illustrated in figure 13.2. The end result is a pattern where sections of the same geometric or floral motif, stitched with the same color thread, reflect light differently because of the different directions in which they were stitched.

Figure 13.1. Detail of the central motif embroidered on the Spanish sampler by Rosa Lópes.

Figure 13.2. Detail of geometric designs seen in 18th century Spanish sampler by Rosa Lópes.

Concluding Remarks

The twelve dechados used as inspiration for this essay are all excellent representatives of the samplers made by Spanish girls and young women during the late 18th century and first half of the 19th century. Each has unique attributes but is also well aligned with recognized Spanish needlework traditions and the changes in those traditions over time. Especially noteworthy is the excellent craftsmanship embodied in the dechados reviewed – suggesting high quality instruction and attentive students who took their needlework education seriously. This can be seen in the girls’ careful attention to detail when executing complex decorative borders, bands, and motifs, as well as the successful use of stitches that result in a dechado whose reverse side is as neat the front. Complementing the excellent craftsmanship is a wonderfully pleasing aesthetic where the carefully orchestrated but subdued color palettes serve to showcase the girls’ work rather than overshadow their efforts.

Bibliography

- Checa Cremades, Fernando. Los Inventarios de Carlos V y la Familia Imperial, Vol. 1. Madrid: Fernando Villaverde, 2010, 1172-1173.

- Del Álamo Martínez, Constancio. “La Colección de Dechados de la Hispanic Society of America, New York.” Datatextile, no. 3 (2000): 4-21.

https://raco.cat/index.php/Datatextil/ article/view/280693 - Espigado Tocino, Gloria. Aprender a Leer y a Escribir en el Cádiz del Ochocientos. Cádiz: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Cádiz, 1996.

- González Elicabe, Ximena & Friederike Reinke, Johanna. “Los Dechados Como Documentos Bordados. Una Historia de Habilidades y Sabiduría Femenina.” Cuadernos del Centro de Estudios en Diseño y Comunicación. Ensayos, no. 261 (2025):17-47.

- González Mena, María Ángeles, Colección pedagógico textil de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid: Estudio e Inventario. Madrid: Editorial Complutense, 1994.

https://educacion.ucm.es/4-coleccion-pedagogico-textil

- May, Florence Lewis. Catalogue of Laces and Embroideries in the Collection of the Hispanic Society of America. New York: Hispanic Society of America, Order of the Trustees, 1936.

- Pino, Ana María Ágreda. "Artes Textiles y Mundo Femenino: El Bordado." Concha Lomba Serrano, Carmen Morte Garcia, & Mónica Vázquez Astorga (eds.) Las Mujeres y el Universo de las Artes. Zaragoza: Institución Fernando el Católico, 2020, 55-82.

https://ifc.dpz.es/recursos/publicaciones/38/38/04agreda.pdf

- Segura Lacomba, Maravillas. Bordados Populares Espanoles. Madrid: Instituto San Jose de Calasanz de Pedagogia, 1949.

- Stapley, Mildred. Popular Weaving and Embroidery in Spain. New York: W. Helburn, Inc., 1924 (translation of the original, Tejidos y Bordados Populares Españoles, by the author.)

https://reader.library.cornell.edu/docviewer/digital?id=hearth4613266

About the author:

Dr. Lynne Anderson is founder and Director of the Sampler Consortium International, a membership organization of individuals and organizations dedicated to the study of historic samplers worldwide (samplerconsortium.org). She is also Director of the Sampler Archive Project, a nationwide effort to locate, photograph, and document all American samplers, making the images and information available to scholars and the public online in a user-friendly searchable database (samplerarchive.org).

Contact Lynne at lynneandrs@gmail.com

Follow Lynne on Instagram @samplercentral