Upcoming & Current Exhibitions

(To skip to our Articles section click here)

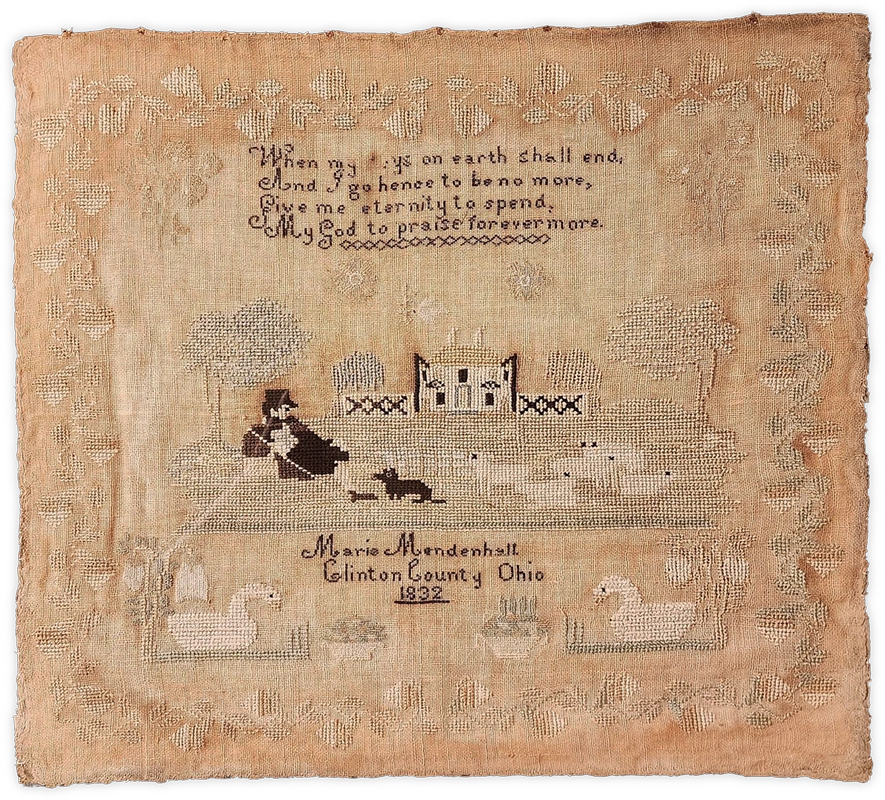

Heartland: The Stories of Ohio Through 250 Objects

Andrew Richmond and Hollie Davis, Curators

Decorative Arts Center of Ohio

145 East Main Street

Ohio sits at the heart of the nation. Heartland: The Stories of Ohio Through 250 Objects invites visitors to discover the people, ideas and moments that have defined the Buckeye State. Spanning themes of resources, people, conflict, culture and change, the exhibition features artifacts that capture both Ohio’s familiar milestones and its lesser-known stories. From handcrafted works and industrial innovations to personal mementos that shaped everyday life, each object reveals a different facet of Ohio’s complex identity. Together, they tell a story of ingenuity, resilience and transformation – showing how Ohio’s communities have both reflected and influenced the nation’s journey. Heartland celebrates the shared experiences that continue to connect Ohioans to one another and to the country at large

This exhibition is presented with support from the Fox Foundation, Inc., Mahon Design, and Meander Auctions

History Revealed by Schoolgirl Samplers

Lecture at the Norwalk Historical Society

with Alexandra Peters

Saturday, March 7 at 2:00 pm EST

Norwalk Town House

2 East Wall Street, Norwalk, CT

I'll be giving a talk in Norwalk about schoolgirl samplers from 1750-1850, appreciated and understood now as historical documents written by girls on silk and linen with needles. Always highly prized by families, thousands of them have survived, documenting the lives, education and creativity of girls.

There is a companion exhibition at the Norwalk Historical Society Museum displaying samplers and needleworks from the museum's fantastic collection of samplers by Norwalk families, and I'll tell you about that, too!

History Made Visible: The Legacy of Thousands of Schoolgirl Samplers

Lecture by Alexandra Peters presented by the Suffield Historical Society, in collaboration with the Phelps-Hatheway House and Connecticut Landmarks

Sunday, March 15 at 2:00 pm

Suffield Senior Center 145 Bridge Street, Suffield, CT

Samplers stitched by girls show us a very different way to look at the record of women's lives in America, from early settlement through the Industrial Revolution. I'll be talking about how the needlework of girls opens up surprising histories about family, education, and daily life.

The King House Museum and the Phelps-Hatheway House have some real needlework treasures, made by girls from Suffield, and I'll be looking at those and my own collection. This will be live on Zoom as well, so please register!

Vermont Needlework

April 15, 2026

6:00 pm - 7:00 pm EST

Zoom

The Shelburne Museum is presenting the webinar New Research into Vermont Needlework on Wednesday, April 15, from 6 to 7 p.m. EST, Shelburne Museum curator Katie Wood Kirchhoff and the Vermont Sampler Initiative’s Ellen Thompson will explore extraordinary examples of schoolgirl artworks made in Vermont, ranging from traditional samplers and silk-on-silk embroideries to memorials, family registers, and more. This webinar will preview some of the items that will be on display as part of the Shelburne Museum’s 2026 exhibition, On Point: Needlework from the Garthwaite Family Collection. Visit the website (www.shelburnemuseum.org/museum-from-home/ webinars) to register.

Samplers and Young Women: Threading Together Art and Education

August 5, 2025 - April 2026 (Exact Closing Date TBD)

Nashville, TN

On display in the gallery that previously housed Early Expressions: Art in Tennessee Before 1900, Samplers and Young Women: Threading Together Art and Education features an exhibition of Tennessee samplers from the Museum’s collection. Samplers were pieces of needlework often produced by girls and young women as a means of learning. They served a practical purpose of simultaneously practicing stitching, reading, and writing, with the alphabet often featured on the samplers. They were also often signed and dated by their makers, making them significant sources for historical research.

Girls frequently made samplers at schools, and therefore provide important insights into 19th century women’s education in Tennessee. Domestic skills such as needlework were considered essential for women. As part of a refined education, ornamental arts such as music, drawing, and needlework were seen as integral in preparing for the domestic role as a wife and mother, as well as a member of an educated society. Samplers from several female academies in Tennessee, including Locust Grove Female Academy, Spring Hill Female Academy, Cloverdale Male and Female Seminary, and Mr. and Mrs. Hunt’s Female Academy will be featured as part of the exhibition. The style of a particular instructor or school can be observed by comparing samplers produced at these academies.

As samplers often feature the name of the maker, year of completion, and occasionally the location or name of a school, they serve as material records preserving the memories of their creators. Many samplers featured in the exhibit, such as Sarah Ann Brown’s (directly above), also detail the maker’s family genealogy, such as the names and birthdays of their parents and siblings. These provide a valuable resource in researching family history and exploring how girls and young women, whose presence may be limited in other historical archives, created records of their lives.

- Julia Doyle, Curator of Textiles

Stars, Stripes, & Stitches: Textiles & American Identity

March 20-21, 2026

Winston-Salem, NC

The Stars, Stripes, & Stitches: Textiles & American Identity seminar, organized by Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (MESDA), will take place March 20–21, 2026 in Winston-Salem, North Carolina (with a virtual option available). The two-day event will explore how colonial and early American women used textiles — quilts, needlework, and woven baskets — as utilitarian, decorative, and documentary objects to express personal values, aspirations, and identity.

Participants will enjoy a full schedule of lectures, including a keynote by Alden O’Brien, along with opportunities to attend pre-conference workshops and an open-house showing of textiles from MESDA’s collection. Hands-on workshops will cover topics such as coverlet pattern design, needlework inspired by historic samplers, and quilt turning; there will also be guided tours of MESDA’s needlework collection and conversations with curators and scholars.

To register, please visit MESDA’s website at:

https://mesda.org/program/textiles-seminar/

Embroidered Histories

November 29, 2025 – May 24, 2026

Featuring favorite stitches and motifs, embroidery samplers have been used to teach needlework skills and literacy since the 14th century. By the 18th century, these textiles were viewed as works of art in their own right. This exhibition highlights European embroidery samplers from the 17th through 19th centuries in our collection. Through a close look at the samplers’ materials, techniques, and designs, Embroidered Histories explores economic, political, and social developments in Europe during these centuries.

A Century of Massachusetts Samplers, 1739 - 1838

July 2025 - June 2026

A small exhibit of early American samplers made by girls attending school in coastal Massachusetts is on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Curated by Amelia Peck, the samplers are graphically exciting and historically fascinating. Some of the highlights include a 1766 sampler from Salem stitched by Rebekah White; a floral needlework picture “wrought at Mrs. Saunders Academy;” and an 1802 verse sampler with elaborate floral border by Lydia Pearson advocating that girls should split their time between books, needles, and pens. Also included are spectacular examples of family record samplers such as the monumental 1812 work of Hannah Loring of Boston. New to the Met’s collection, and on display for the first time, is a sampler made in 1838 by Boston born Angenett Jackson, a free black girl. She is known to have attended a school established by the Garrison Juvenile Society that met in a classroom in Boston’s African Meeting House. The exhibit is installed in a small gallery off the Richmond Room in the American wing and will remain available to the public until June 2026. Images posted on Instagram July 26 by @antiquesamplers.

Samplers and Young Women

August 5, 2025 - April 2026

The Tennessee State Museum is hosting a sampler exhibition titled “Samplers and Young Women: Threading Together Art and Education” showcasing Tennessee samplers from the museum’s collection. The exhibition opened August 5, 2025 and will continue until April 2026. Building on the research of Jennifer Core and Janet Hasson, authors of a newly released book on Tennessee samplers, the exhibition was curated by Julia Doyle and explores the intersection of female education, art, and needlework. The samplers vary by region (East, Middle, and West Tennessee) and display differences in materials (linen, wool, silk), motifs, stitch patterns, and craftsmanship. The exhibition also features samplers from multiple female academies in Tennessee: Locust Grove Female Academy, Spring Hill Female Academy, Cloverdale Male and Female Seminary, and Mr. and Mrs. Hunt’s Female Academy. The Tennessee State Museum is located in Nashville and is open to the public Tuesday through Sunday.

Gallery Talks for “Sampled Styles” Exhibition

On September 20, 2025 from 11:00 am to 2:00 pm the Quaker Tapestry Museum’s curator will give 45-minute gallery talks about “Sampled Styles,” the museum’s first major exhibition focusing on Quaker samplers (March 8 to December 20, 2025) in Kendal, England. The talks will explore the evolution of styles, regional and institutional variations, and discuss what the samplers communicate about the lives of early Quaker women and girls in England. At the Quaker Tapestry Museum, visitors will also learn about the Quakers’ origins and their impact on society over the last 350 years. From scientific and industrial revolutions to social reform, peace, and the abolition of slavery. Always on display is The Quaker Tapestry, a large-scale collaborative embroidery picturing the history of Quakers in England. The museum is housed in Kendal Friends’ Meeting House, built in 1816 on a site that has been used for Quaker worship for over 300 years. In celebration of Heritage Open Days, both the gallery talks and entry to the museum will be free.

Threads of Life

Embroiderers’ Guild of America Virtual Lecture by Clare Hunter

October 11, 2025 (1:00 pm ET)

Announcing an Embroiderers’ Guild of America Virtual Lecture on October 11, 2025 (1:00 pm ET) by Clare Hunter, based on her book titled “Threads of Life: A History of the World through the Eye of a Needle.” In her words: “Fabric and thread can convey a prayer, trace out a map, proclaim a manifesto, send out a warning, bestow a blessing, celebrate a culture and commemorate lives lived and lost…Sewing is a way to mark our experience on cloth; patterning our place in the world, voicing our identity, sharing something of ourselves with others and leaving the indelible evidence of our presence in stitches held fast by our touch.” Registration at the EGA website opens September 18.

Lecturer: Clare Hunter

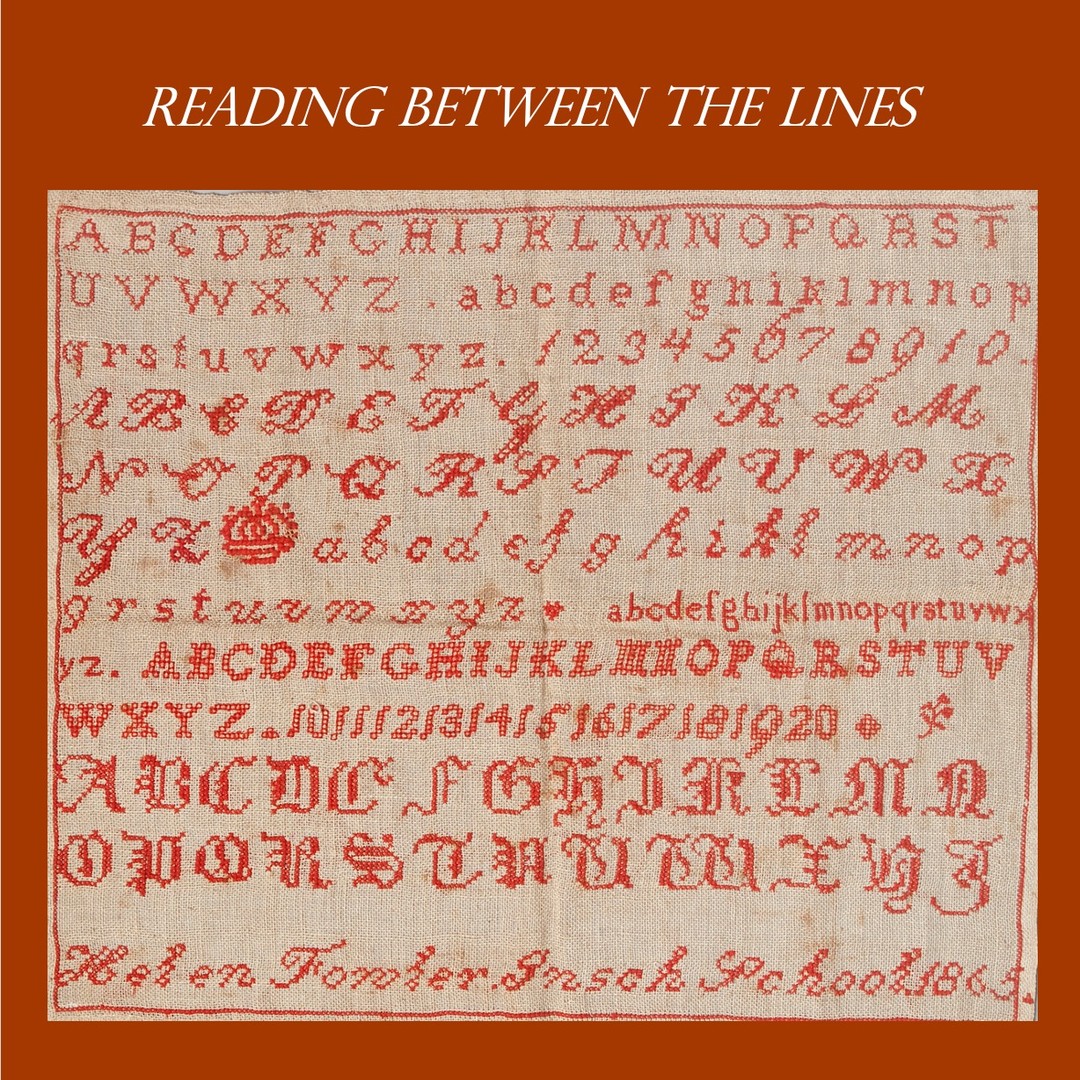

Reading Between the Lines: Embroidered Samplers

14 December 2024-30 November 2025

More than a record of stitches, a sampler was also evidence of the sewer’s industriousness, obedience and virtue. These samplers from our collection provide insights into the lives of the girls who sewed them and the social, political and religious environment in which they lived in the 1700s and 1800s.

Exhibition curated by Morna Annandale.

Articles:

A Sampler’s Story from Sierra Leone

By Matthew Monk, Linda Eaton Associate Curator of Textiles at Winterthur

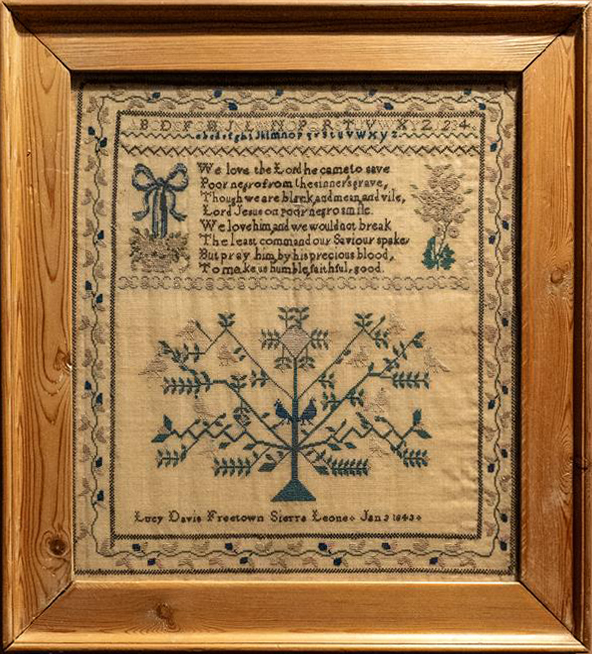

Sampler, Africa, 1843. Museum purchase with funds provided by the Henry Francis du Pont Collectors Circle 2018.0007

On January 3, 1843, Lucy Davis, a Black African girl, completed this sampler at a Church Missionary Society (CMS) school in Freetown, Sierra Leone. Her needlework features a central field divided by a cross-stitched border of repeating X motifs. The upper half contains a verse from Hymn for a Poor Negro, a poem printed in The Missionary Repository for Youth, and Sunday School Missionary Magazine.1 Missionaries across the expanding British Empire used literature like this to Christianize and anglicize African youth and reinforce British colonial hierarchies of race and class:

“We love the Lord he came to save

Poor negro from the sinner’s grave,

Though we are black, and mean, and vile,

Lord Jesus on poor negro smile.

We love him, and we would not break

The least command our Saviour spake,

But pray him, by his precious blood,

To make us humble, faithful, good.”

Flanking the verse are a basket of flowers tied with a bow on the right and a spray of blooms on the left. The lower half of the linen ground features a stylized tree filled with birds with Davis’s name, location, and the date stitched below. A leafy vine border, framed by long-arm cross stitches, surrounds the entire composition.

Only twenty-six samplers from CMS schools are known to survive, and few student records exist beyond the needlework itself. However, one teacher’s name is known: Jane Hickson Boston Young (1810–1841), a Eurafrican woman educated at a CMS school in the Rio Pongo region (now the Republic of Guinea). Jane learned needlework from an African American colonist—referred to only as “Nova Scotian”—who had remained loyal to Britain during the American Revolution and later immigrated to British-controlled Africa from Nova Scotia.(2)

Lost Voices from Australia's History

Article by Mary McGillivray on Australia’s ABC news (July 9, 2025) about two Botany Bay samplers stitched by Scottish schoolgirls. Scholars are divided as to why 10-year-old Margret Begbie, whose undated sampler is in the National Museum of Australia, and Euphemia Doieg, whose 1814 sampler is in the Royal Scottish Museum, stitched motifs of sailing ships flying the English naval flag landing in a harbor labeled Botany Bay. The article explores explanations proposed by sampler scholars. In the words of National Museum of Australia curator Laura Cook, "The flow of objects, images and descriptions from New South Wales back to Britain formulated an imagined idea of the new colony and the people who lived there." Lorinda Cramer, who wrote the book “Needlework and Women’s Identity in Colonial Australia” suggests, the girls were instructed to stitch this scene as "a powerful moral lesson" about "the consequences of bad conduct which could result in transportation [to a penal colony], perhaps for life".

19th century European sewing manuals recommended that girls be proficient in simple sewing by the age of six, and spend at least one hour a day practicing. (Supplied: National Museum of Australia)

Stitching a Lineage

Youtube presentation by Erica Lome, Curator of Collections at Historic New England

Now available on YouTube – a recording of the presentation on August 22, 2025 by Erica Lome, Curator of Collections at Historic New England, titled "Stitching a Lineage: Embroidered Coats of Arms in Eighteenth-Century Boston." Hosted by American Ancestors, Erica explored18th century embroidered coats of arms made in Boston, one of the city’s most prolific and enduring forms of schoolgirl needlework. Showcasing the skill and dedication of their makers, embroidered coats of arms are examples of genealogical material culture, documenting that young colonial women were integral to the articulation and preservation of their family history. Discussed against the backdrop of America’s conflict with Britain, Erica points out the major components of heraldic schoolgirl needlework using an unfinished diamond-shaped black silk embroidery by Mary Jones, whose grandson was Henry David Thoreau. Also discussed is a 1740 coat of arms by 13-year-old Rachel Leonard and a 1745 example by Katherine Greene of Warwick, RI. Popular between 1740 and 1790, embroidered coats of arms speak to the desire among Boston’s elite families to own a representation of their ancestry and lineage that could be displayed in their homes.

Spotlight: In-Depth Dive

into Noteworthy Needlework

From time to time, we post in-depth studies of significant samplers, or groups of samplers

A New Discovery: The Nancy Bozyol Lane Sampler Made at the Sarah Stivours School in Salem, Massachusetts

Article published 8/21/2025 with permission of the author, © 2025 Mary Yacovone

Spotlight: In-Depth Dive

into Noteworthy Needlework

From time to time, we post in-depth studies of significant samplers, or groups of samplers

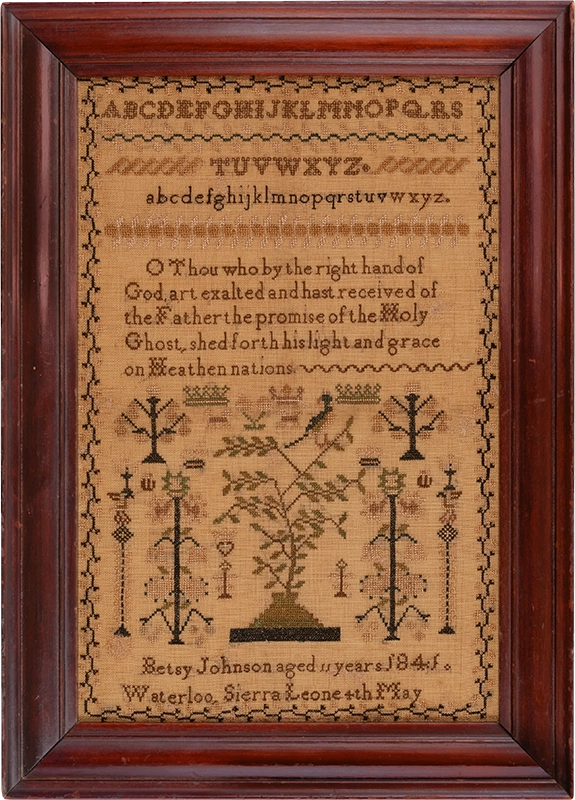

Mission Samplers from Sierra Leone: Traces of a Black Woman’s Career in the Church Missionary Society, c.1811 to 1841, by Silke Strickrodt, PhD

Article published 3/13/2025 with permission of the author, © 2025 Silke Strickrodt

Needlework and Identity

Volume 58, Number 1 | Spring 2024

An article by Erica Lome and another by Marla R. Miller

The most recent issue of the “Winterthur Portfolio” (Volume 58, Number 1 | Spring 2024) includes two articles by scholars who spoke at Winterthur’s October 2022 needlework conference “The Needle’s I: Stitching Identity.” This special issue of WP is the first of two issues that feature expanded versions of the talks presented at the 2022 symposium. Included in this first issue are (1) an Introduction to the proceedings titled “Needlework and Identity” by Laura Johnson, former curator of textiles at Winterthur and editor for this special issue; (2) an article by Erica Lome titled “Stitching a Lineage: Embroidered Coats of Arms in Eighteenth-Century Boston,” which explores the silk on silk embroideries from colonial Boston that provided adolescent girls with opportunities to preserve and perpetuate their family’s heritage; and (3) an article by Marla R. Miller, “Monuments in Flax and Wool: The Memory Work of Heritage Textiles,” providing a close analysis of a single embroidered object as a venue for historical memory making across time and families.

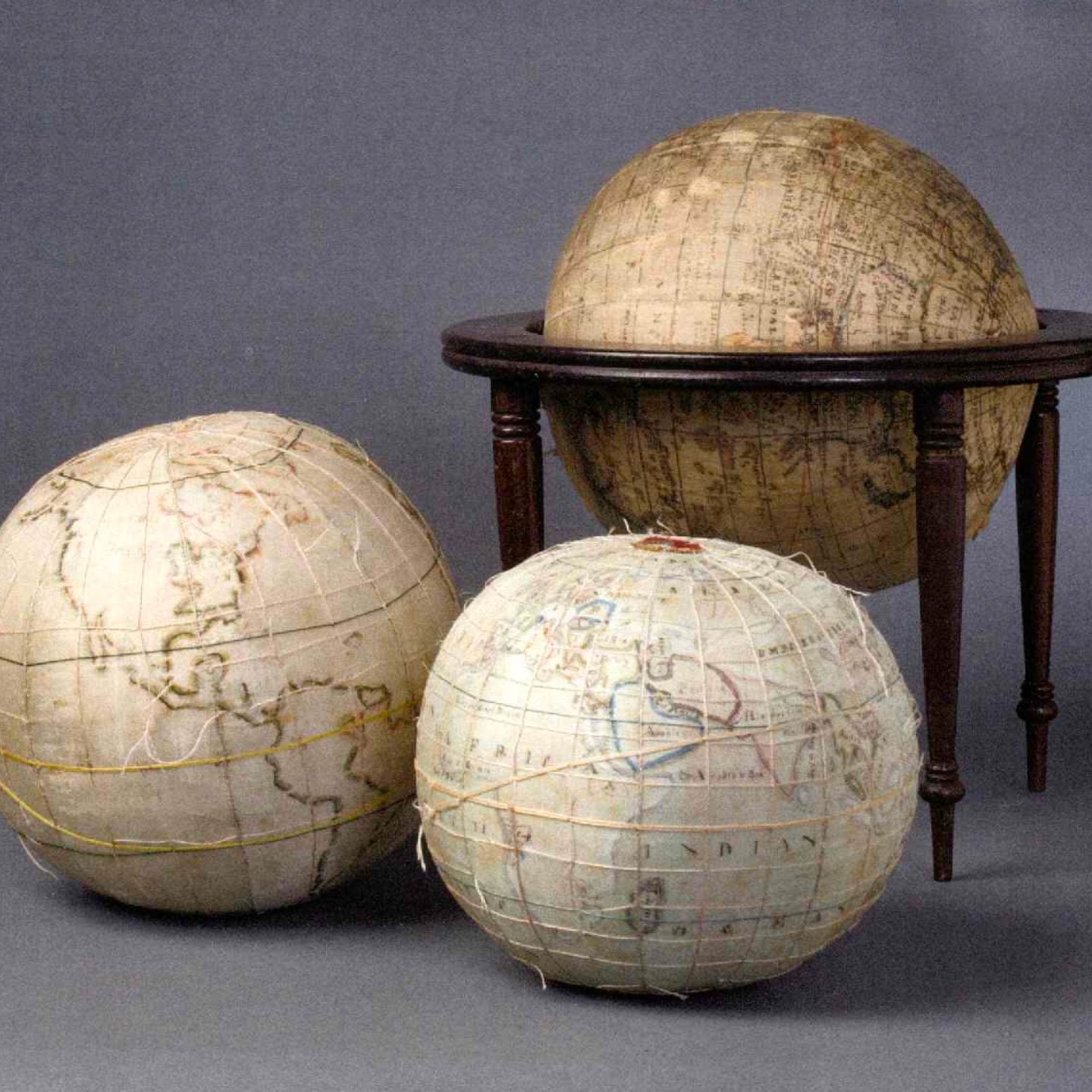

World of Learning: Embroidered Globes

Mary Uhl Brooks

Article in “Piecework Magazine” (Winter 2024) by Mary Uhl Brooks entitled “A World of Learning: The Embroidered Globes of Westtown School.” Unique among schoolgirl embroideries are the terrestrial and celestial globes created by female students attending Westtown School, a Pennsylvania Quaker boarding school established in 1799. Although it is unknown who had the idea that girls should construct globes to enhance their study of geography and astronomy, there are at least 44 known embroidered globes, six of which are celestial. Five of the celestial globes are paired with a terrestrial globe by the same maker, suggesting that girls probably made the terrestrial globes first and that only some went on to make a second one. The globes are about six inches in diameter and made of silk, linen, and raw wool. Continents and other geographic locations, as well as lines of longitude and latitude, are marked with thread, ink, and watercolor. Mary Uhl Brooks is the former archivist of Westtown School and author of “Threads of Useful Learning: Westtown School Samplers,” published in 2015.

(Above) Celestial globe made by Phebe Peirce while attending Westtown Boarding School. Shown is a view of the southern sky, including the constellation Centaurus, represented by a half-man, half-horse figure. Courtesy Special Collections, Kenneth Spencer Research Library, University of Kansas.

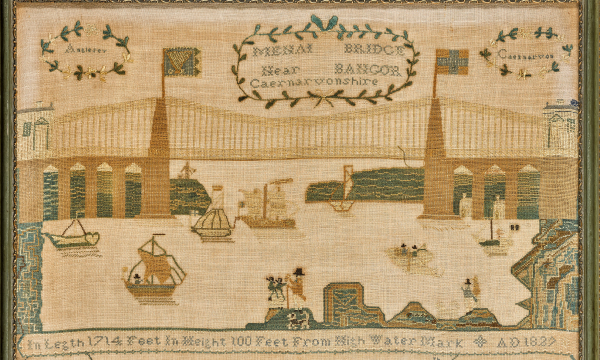

19th Century Needlework of Celebrated Menai Bridge at Risk of Leaving the UK

Mary Anne Hughes, 1827

Article in the BusinessNewsWales about an export ban placed on a needlework picture of the Menai Bridge. Stitched by 11-year-old Mary Anne Hughes in 1827, the embroidered picture depicts the suspension bridge over the Menai Strait, which connects the island of Anglesey to mainland Wales and was the longest suspension bridge in the world when constructed in 1826. The needlework was auctioned by Sotheby’s on April 11, 2024 for £13,970. Felt to be a national treasure documenting an important historical event, the export ban was put in place to provide time for a British institution to come up with the money to purchase the sampler from auction’s high bidder. Now valued at £14,564 (including the buyer’s premium), the ban expires January 7, 2025.

Read the article here

Sampler by Mary Anne Hughes depicting the Menai Bridge

The Pocketbooks and Purses of Mary Wright Alsop

A life documented in craft

Susan Holloway Scott

Article in “Piecework” by Susan Holloway Scott exploring the life history, education, and needlework of Mary Wright Alsop (1740-1829), from Middletown, CT. The only daughter of affluent parents, Mary is believed to have attended Sarah Osborn’s school in Newport, Rhode Island, where she became highly skilled in needlework, making four tent stitch pictures (one for each season), chair covers, and at least one pocketbook embroidered in queen stitch for her father. After her marriage to Richard Alsop in 1760 Mary continued to embroider a variety of practical and decorative items, many of which survive. Of equal interest, however, is the description of Mary’s responsibilities after the unexpected death of her husband, and her careful management of his mercantile business and real estate holdings as the sole executer of his large estate, all while raising eight children under the age of 15. Great article about a many faceted woman in early America for whom needlework was an integral part of life.

Mrs. Richard Alsop, 1792, oil on canvas, 45 5⁄8 x 36 1⁄8 in. (115.8 x 91.8 cm)

Museum purchase and gift of Joseph Alsop, 1975.49.1.

Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum

Pauline Fortier’s Sampler: A Material Record of Early-19th-Century New Orleans

Lily Higgins

Article by Lily Higgins in the Decorative Arts Trust Bulletin (October 18, 2024) about an 1815 sampler in the Historic New Orleans Collection made by Pauline Fortier (1805-1877) while a student at the New Orleans Ursuline Convent. The author reports on her visit to the convent, facilitated by a research grant from the Decorative Arts Trust, and shares results of genealogical research into the life of the sampler maker and her family. Her research revealed that Pauline’s family were major slave owners in the area and witnesses to the relatively unknown 1811 German Coast Uprising of enslaved laborers from plantations on the Mississippi River.

Figure 1. Pauline Fortier, Sampler, 1815, New Orleans. Cotton thread on linen with cotton backing. HNOC, 2004.30.

Photo by author.

A Tale of Two Samplers

Nov 27, 2024

by Lea C. Lane

In June 2024, the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts welcomed eight fellows to Winston-Salem for the 47th annual Summer Institute program. The Decorative Arts Trust has long been a foundational supporter of this program, and through the generosity of William and Susan Mariner, sponsored one of our fellows.

Colonial Williamsburg’s Jackie Mazzone attended thanks to the William C. and Susan S. Mariner Fellowship for Emerging Museum Professionals sponsored by the Decorative Arts Trust. A native New Englander, Jackie’s work has spanned the realms of both curatorial work and craftsmanship, specifically as a cooper at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

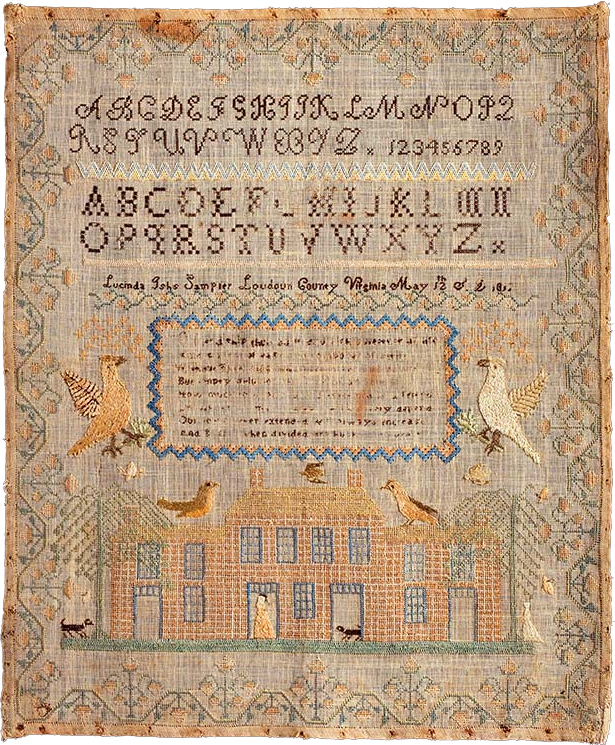

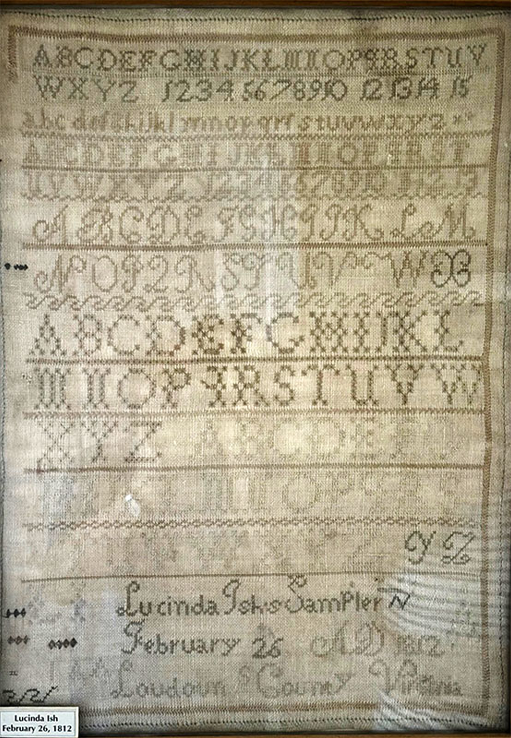

Like all Summer Institute scholars, Jackie focused her research on a single object from MESDA’s collection: in her case, a large needlework sampler worked by Lucinda Ish in 1812 (figure 1). Jackie quickly realized that the story was larger than a single expanse of linen and silk. There were, in fact, two surviving samplers by Lucinda. MESDA’s founder, Frank L. Horton, acquired our sampler for the museum in 1967, but the other, slightly earlier textile continues to be treasured by her descendants (figure 2).

(Figure 1) Lucinda Ish, Sampler, May 1812,

Loudon County, VA. Silk on linen. MESDA, 2033.6.

(Figure 2) Lucinda Ish, Sampler, February 1812,

Loudon County, VA. Silk on linen. Private collection.

SPOTLIGHT: IN-DEPTH DIVE INTO A NOTEWORTHY SAMPLER

Amy Finkel

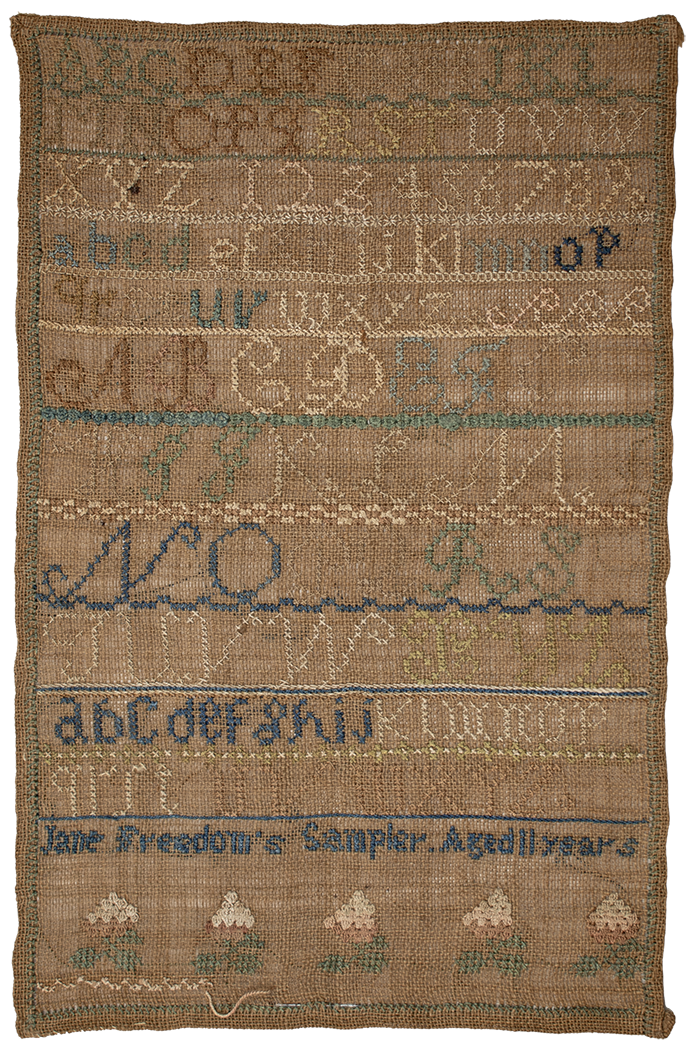

A great rarity, this sampler was made by an 11-year-old free Black girl, Jane Freedom, living in Norfolk, Litchfield County, Connecticut, about 35 miles northwest of Hartford. The needlework presents relatively simple alphabets and a row of strawberries along the bottom. These were accomplished in the queen’s-stitch, a sophisticated technique that was generally taught only to advanced samplermakers. Remarkably, Jane’s needle is still in her sampler, nearby an incomplete line of stitching at the bottom of the sampler. To learn more about Jane Freedom's sampler and her life, please read our article published on our site here

Video: Embroidered Lives, South County Samplers and Their Stories

curated by Lynne Anderson at the Gilbert Stuart Birthplace and Museum

Samplers at the Met

curated by Amelia Peck

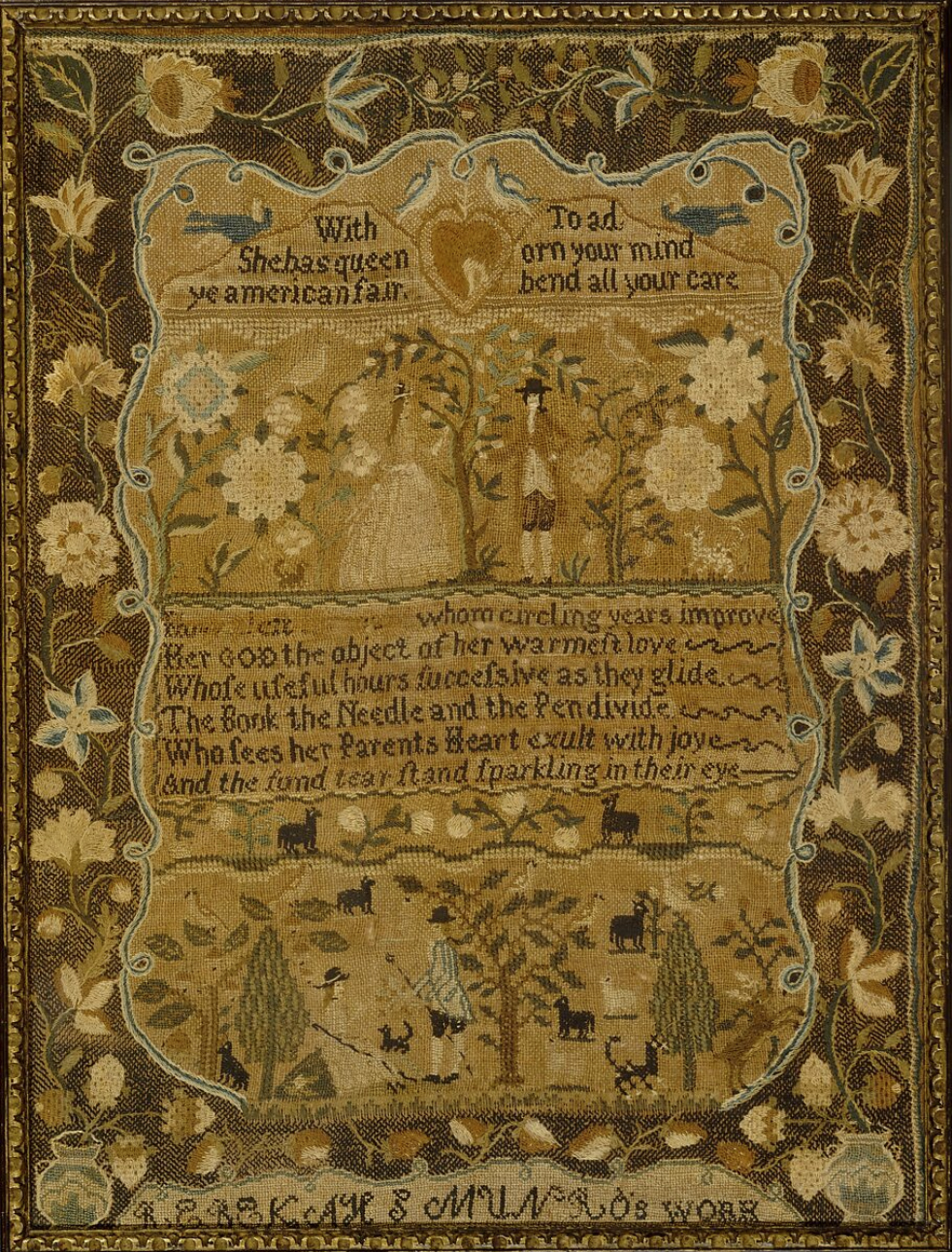

Eight 18th century American samplers are on display in a small exhibit in the American Wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. Curated by Amelia Peck, the samplers were made between 1721 to 1795 and are showcased in an intimate gallery off the Richmond Room. One of the stars is a sampler by Rebekah White, stitched in 1766 in Salem, Massachusetts. Rebekah was born July 18, 1754, the daughter of Benjamin and Elizabeth (Miller) White. Her sampler is very similar to the 1766 sampler by Susannah Saunders, also of Salem, that was formerly in the Betty Ring collection. Both samplers showcase the long diagonal filling stitches common to many 18th century samplers made in Salem, a technique that was apparently adopted by multiple area teachers. Clearly Rebekah and Susannah knew each other and attended school together. Another stunning sampler in the exhibit was stitched in 1792 by Martha (Patty) Coggeshall of Bristol, Rhode Island. Patty’s sampler was probably embroidered under the instruction of Anne Bowman Usher (1723–1793), who ran a successful school for girls in Bristol from 1774 to 1793. Samplers from the school have a distinctive fully stitched black background and distinctive motifs such as a man playing a flute and a long-tailed bird in flight. Also included in the exhibit are the following samplers.

Eight 18th century American samplers are on display in a small exhibit in the American Wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. Curated by Amelia Peck, the samplers were made between 1721 to 1795 and are showcased in an intimate gallery off the Richmond Room. One of the stars is a sampler by Rebekah White, stitched in 1766 in Salem, Massachusetts. Rebekah was born July 18, 1754, the daughter of Benjamin and Elizabeth (Miller) White. Her sampler is very similar to the 1766 sampler by Susannah Saunders, also of Salem, that was formerly in the Betty Ring collection. Both samplers showcase the long diagonal filling stitches common to many 18th century samplers made in Salem, a technique that was apparently adopted by multiple area teachers. Clearly Rebekah and Susannah knew each other and attended school together. Another stunning sampler in the exhibit was stitched in 1792 by Martha (Patty) Coggeshall of Bristol, Rhode Island. Patty’s sampler was probably embroidered under the instruction of Anne Bowman Usher (1723–1793), who ran a successful school for girls in Bristol from 1774 to 1793. Samplers from the school have a distinctive fully stitched black background and distinctive motifs such as a man playing a flute and a long-tailed bird in flight. Also included in the exhibit are the following samplers.

For images and more information on all of the samplers listed, check out the 18th century American samplers in the Metropolitan Museum’s online collection (link below). Mary Munro, 1788, Mary Balch School in Providence, Rhode Island Peggy Ingraham, undated but she born in 1778, Bristol, Rhode Island Mary Austin, 1784, of Salem, Massachusetts Mary Waine, 1795, of Boston, Massachusetts Abigail Ridgway, 1795, unknown origin.

See these samplers and many more here

Marvelous Maps

Five schoolgirl embroideries of the

Plan of the City of Washington ca. 1800

by Virginia Whelan, Textile Conservator,

NSCDA Sampler Survey chair, Pennsylvania Society

Article by Virginia Whelan in the NSCDA publication “Dames Discovery” (Spring/Summer 2023, Vol. 33, No. 1, p. 8-9) entitled “Marvelous Maps.” The article discusses five very detailed silk-on-silk map samplers featuring “the plan of the city of Washington.” Believed to have been stitched by girls attending school in Alexandria, Virginia circa 1800, each embroidery is unique but all share enough similarities to attribute them to the same instructor. Virginia discusses the shared features but also highlights the subtle differences (e.g., various spellings for the Potomac River) and provides explanations for why these differences might exist. Information is also provided about each of the five sampler makers and current ownership for all five embroideries. Virginia Whelan is a textile curator and owner of Filament Conservation Studio in Pennsylvania. She is also chair of the NSCDA Sampler Survey.

How to Research an Antique Sampler

Lecturer: Cindy Steinhoff

Original Lecture Date: Sunday, June 11, 2023

Recording of lecture available for purchase

An antique sampler reveals some of its physical characteristics and often some information about the girl who stitched it, but what else can it tell us? Cynthia Shank Steinhoff will discuss how she learns more about the samplers she collects and researches. The result is a full documentation of a sampler’s appearance and history. Many of the characteristics that she identifies for older samplers can be used to provide a full description of a needlework piece made today.

Cynthia Shank Steinhoff is the director of the library at Anne Arundel Community College, where she has been a member of the faculty since 1983. A graduate of Edinboro State College (now Edinboro University of Pennsylvania), she also holds a Master of Library Science degree from Clarion University of Pennsylvania and a Master of Business Administration degree from University of Baltimore.

Cynthia is a stitcher, sampler collector, and needlework researcher. She began stitching as a young girl and still owns the first set of stamped pillowcases that she made. Her collection of samplers includes works by girls in Delaware, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey, among other states, and from Scotland, England, and Ireland. The oldest sampler in her collection was made in England in the 1730s. Her current areas of focus are samplers made in Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Delaware, and those stitched by Quaker girls. She researches many aspects of her needlework pieces, including stitches and materials used in the samplers, the stitchers’ lives, and connections between her pieces and others in museums and private collections.

Cynthia contributed to and copy-edited Wrought with Careful Hand: Ties of Kinship on Delaware Samplers, by Dr. Lynne Anderson and Dr. Gloria Seaman Allen, the catalog that accompanied an exhibition of 60 Delaware samplers at the Biggs Museum of American Art in Dover, Delaware, in 2014. She is the co-author with Gloria Seaman Allen of Delaware Discoveries: Girlhood Embroidery, 1750-1850, published in 2019, and is also its editor. Cynthia wrote Delaware Schoolgirl Samplers, an essay on the M. Finkel and Daughter web site. She has given presentations about samplers at numerous needlework guilds, Winterthur’s biennial needlework conference, Penn Dry Goods Market, and Sewell C. Biggs Museum of American Art in Dover, Delaware.

A member of the Annapolis Historic Sampler Guild and Loudoun Sampler Guild, Cynthia also belongs to three chapters of the Embroiderers Guild of America – Constellation, Washington DC, and CyberStitchers, the EGA’s online chapter. She is first vice president of Anne Arundel Genealogical Society in Maryland.

When not researching samplers, Cynthia can be found stitching (usually a sampler), reading a mystery novel, and hanging out on the family dog.

Link to purchase lecture recording of this past event

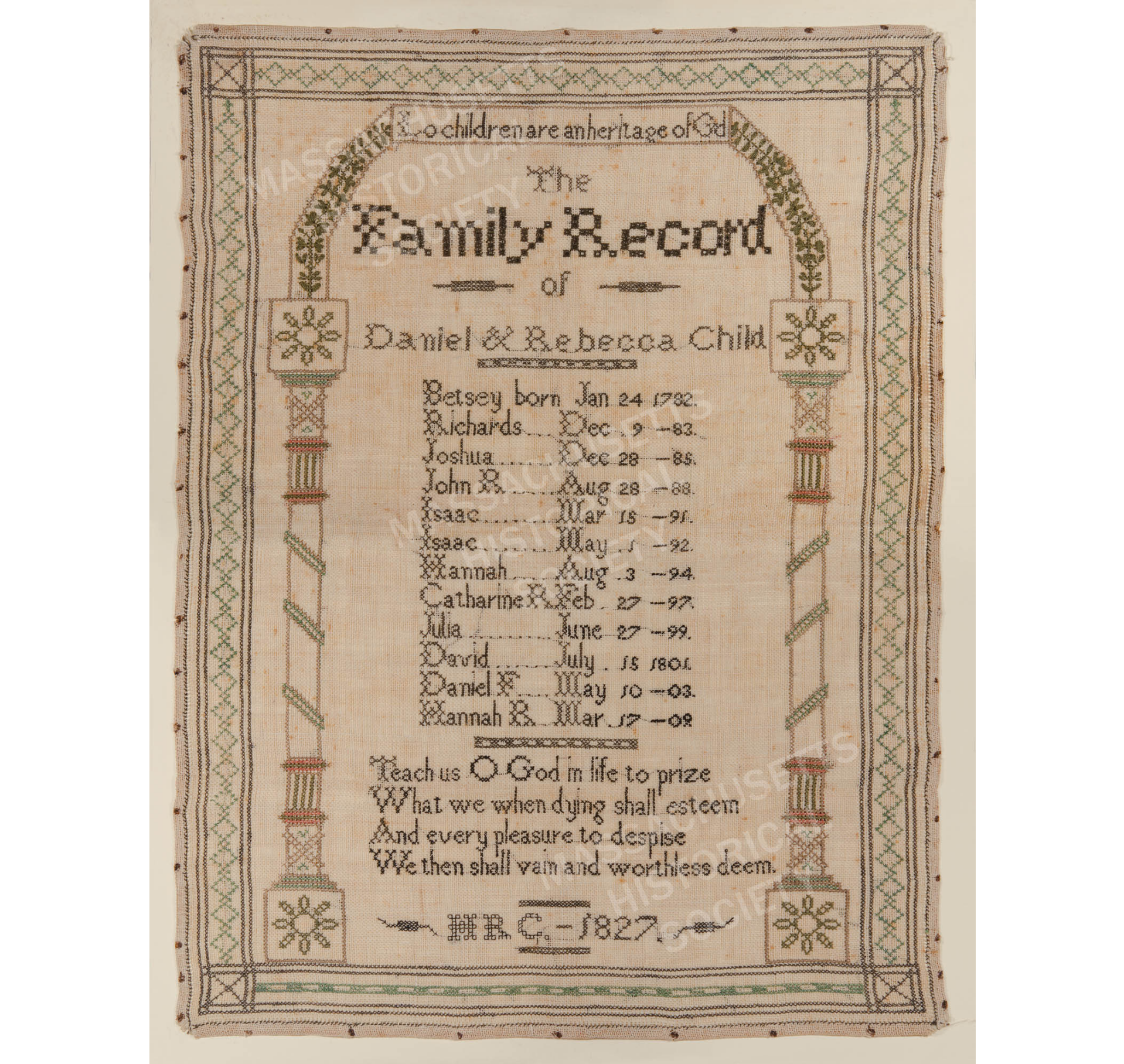

“Lo Children are an heritage of God”: a Family Record Sampler of the Child Family

Article via Massachusetts Historical Society, May 2023; Object of the Month

Recording family history

While most people are familiar with published family genealogies and manuscript lists of ancestors in musty family Bibles, genealogy also played a starring role in the decorative arts. One of the most interesting is the family record sampler, which first appeared in the late 18th century and reached its peak of popularity between 1820 and 1830, particularly in New England. Whereas girls of a previous generation might have expressed their family pride by stitching an elaborate coat of arms, as Sally Cobb Paine did in the 1760s, by the turn of the century, girls stitched records that were less formal and more focused on recording their own family unit. As Peter Benes notes, family unity in these records was demonstrated in a common and easily understood visual vocabulary, “by interlocking chains, by adjacent circles, by standing architectural structures, and by planted grids or ‘fields’ of names.”

This needlework sampler stitched by Hannah Richards Child in 1827

memorializes the family of Daniel and Rebecca Richards Child ofWest Roxbury and Newton, Massachusetts.

Black cotton thread on loosely woven natural linen, 1827, 54.7 cm x 42 cm

The Child family sampler

Hannah Richards Child’s 1827 family record sampler contains elements of Benes’s formula. Strong twin pillars enclose the family’s names within, crowned with an arch and the phrase “Lo Children are an heritage of Gd,” from Psalms 127:3, which continues “Like arrows in the hands of a warrior are children born in one’s youth. Blessed is the man whose quiver is full of them.” Hannah’s choice of psalm serves as both an affirmation of her strong religious faith and a loving tribute to her father. After her mother Rebecca died in 1826, Hannah—according to her own obituary—"had devoted herself assiduously to her surviving parent, consoling him under many trials, through which he has recently been called to pass, and directing his house with a degree of judgment, prudence, and affection that are seldom equalled.”

Within the pillars, Hannah recorded the names and birthdates for herself and her 11 siblings, although by the time she stitched her family register, three of her siblings and her mother had died. Two names are repeated on the list—Isaac and Hannah. At the time, child mortality was not uncommon and when a child died, the next child of the same sex would sometimes be named for his or her predecessor, often within the same year. This occurred twice in the Child family. The first Hannah was born in 1794 and stitched her own sampler in 1805, four years before her death in January of 1809 at the age of 14. Our sampler maker, born later that year, was christened Hannah, a name that proved unlucky for her as well. Four years after stitching this sampler, Hannah Richards Child met a tragic end and was glowingly eulogized in the 13 April 1831 edition of the Columbian Centinel:

"Died, in Newton, on the 5th inst. Miss Hannah R. child, aged 22, youngest daughter of Mr. Daniel Child. The sudden death of this young woman, together with the distressing circumstances of it, has cast a gloom over the whole neighbourhood. To see one, thus lovely and excellent, at one moment in perfect health, and, at the next, torn from us by death in one of its most heart-rending forms, is truly distressing. In the afternoon of that day, her aged father left his home to be present at an examination of a neighbouring school. On his return, about five o’clock, finding her not in the house, and having waited a short time, in momentary expectation of her return he became alarmed. The neighbours were assembled, and search was made. At 8 o’clock in the evening, her remains were found at the bottom of the well, near the house. It appears that she had gone to the well for water; and that, in reaching over the curb, to lift out the bucket, she was precipitated to the bottom of the well, that was twenty-five feet deep, with fourteen feet of water. Medical aid was at hand, and every effort made to rekindle the spark of life; but it was quenched.

The scene presented by this event was heart-rending to those who witnessed it. For several years since the death of her mother, this affectionate daughter had devoted herself assiduously to her surviving parent, consoling him under many trials, through which he has recently been called to pass, and directing his house with a degree of judgment, prudence, and affection that are seldom equalled. To see this old man, in the increasing alarm for his daughter’s safety, in the apprehension for her fate, that became more dreadful with every moment’s delay, and the yet evident fear to know the worst, and at last in the agonies of despair, when he saw that she was dead, must have touched every heart that was not itself dead to feeling. To her father no blow could be more painful, to her brother and sisters none more severe—by the circle—the large circle—of her friends, none more sensibly felt. The void that this death has left in society will not be easily filled. But all her friends have the consolations that spring from their religious convictions and hopes, and the beauty and excellence of her character. We bow before the mysterious movements of God’s holy providence, and hope and trust that such as may have been influenced by her example to follow in her steps, may hereafter be united with her in the rewards which have been graciously set before our hopes, as motives to virtue, in the gospel in which the deceased trusted till her death, and which she adorned in her life."

For further reading

The samplers worked by both Hannah Child and Hannah Richard Child were given to the Massachusetts Historical Society along with the papers of their brother John Richards Child.

The Society also holds the papers of their brother Daniel Franklin Child.

The MHS also owns a family record sampler by Sally Whitcomb of Randolph, Mass., ca. 1809.

Benes, Peter. “Decorated New England Family Registers, 1770 to 1850,” in The Art of Family: Genealogical Artifacts in New England Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2002.

Child, Elias. Genealogy of the Child, Childs and Childe Families Utica, N.Y.: Curtiss & Childs, 1881.

Huber, Stephen and Carol Huber. Samplers: How to Compare and Value London: Octopus Publishing Group, 2002.

Ring, Betty. Girlhood Embroidery: American Samplers & Pictorial Needlework 1650-1850 New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1993.

Gracious and Artful Devices for the Adornment of Life

BY WILLIAM DEGREGORIO AND CHRISTIAN JUSSEL

An early step in needlework’s reappraisal as an art form was the Exhibition of Old English Tapestry Pictures, Embroideries and Samplers of 1900, organized by the former editor of the Art Journal, Marcus B. Huish, at the Fine Arts Society in London. As he wrote in the large illustrated catalogue that appeared later that year, popular interest in the exhibition was extraordinarily high, precisely because “almost every visitor possessed some specimen of the craft, but few had any idea that his or her possession was the descendant of such an ancestry, or had any claim to recognition beyond a quite personal interest.” Only when needlework was removed from its domestic context and viewed en masse did the public begin to accept its value. It took a “museological” approach to elevate estimation of this material, and Huish cited no less an authority than John Ruskin in arguing for needlework’s fundamental place in the English museum landscape. The Illustrated London News hoped that the “publicity thus given to the primitive phase of our national art may draw other specimens from their hiding-places.”

Subsequently, in a fulfillment of this wish, the numerous exhibitions that showcased English needlework in the interwar period (1919–39), often staged for charities, brought together large quantities—up to 600 pieces in some cases—of embroidery, impressing the public with the sheer mass and brilliancy of this material. Typically viewed in sometimes sad country-house contexts, domestic needlework of the seventeenth century did not have a stellar artistic reputation. However, the needlework caskets (Fig. 1), baskets (Fig. 4), framed panels (Fig. 5), and trinkets (Fig. 6) collected by Percival Griffiths, Sir William Burrell, William Hesketh Lever (Lord Leverhulme), Sir William Plender, Sir William Lawrence, Frank Ward, and Sir Frederick Richmond were carefully chosen to be the best of the best in connoisseurial terms, and when these objects were presented in large numbers—often with the endorsement of the omnipresent exhibition patron Queen Mary—their reputation and interest steadily grew.

Needlework picture of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, English, c. 1650.

15 1⁄2 by 19 1⁄2 inches. Collection of Joseph P. Gromacki.

Article continued on The Magazine Antiques

Resources:

Presented by Margi Hofer, Museum Director and Vice President of the NYHS, it's a deep dive into Rosena Disery, a student at New York City’s African Free School, and her highly significant 1820 sampler. Hofer includes a great amount of information about the school and also its students along with fascinating information about the lives of Rosena, her husband and family - highly successful caterers in NYC. The New York Historical Society also holds the African Free School’s records and papers.

This sampler, and much information, is in the archives of our website. Put "rosena" in the search box upper right on any page of our site (of course you can use this for any other search). We are proud to have owned, researched, conserved and framed the sampler before NYHS acquired it, ten years ago.

Article in The Magazine Antiques (July 3, 2020) by Dr. Gene R. Garthwaite

visit https://www.themagazineantiques.com/article/new-light-notes-on-vermont-schoolgirl-embroidery/

visit Bennington's website for more information on this sampler from 1835.

Check out a recorded Zoom presentation (in Spanish, password is: 0p%eR140) about school girl embroidery in Mexico City from the College of San Ignacio De Loyola, Vizcaínas, founded in 1767

National Museum of American History (NMAH) in Washington, DC.

The exhibition is one in many ways in which the various Smithsonian museums have chosen to honor the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th amendment giving women the right to vote.

The exhibition will be at the NMAH for two years, after which it will be a traveling exhibition and be on display at five to seven other museums in the country 2023-2025. https://americanhistory.si.edu/

by Stacey Fraser (she/her/hers)

Scottish Rite Masonic Museum & Library

Assistant Curator

Lexington Historical Society, Massachusetts

visit lexingtonhistory.org

by Aimee Newell

Luzerne County Historical Society, Pennsylvania

visit luzernehistory.org

Archived Past Exhibitions:

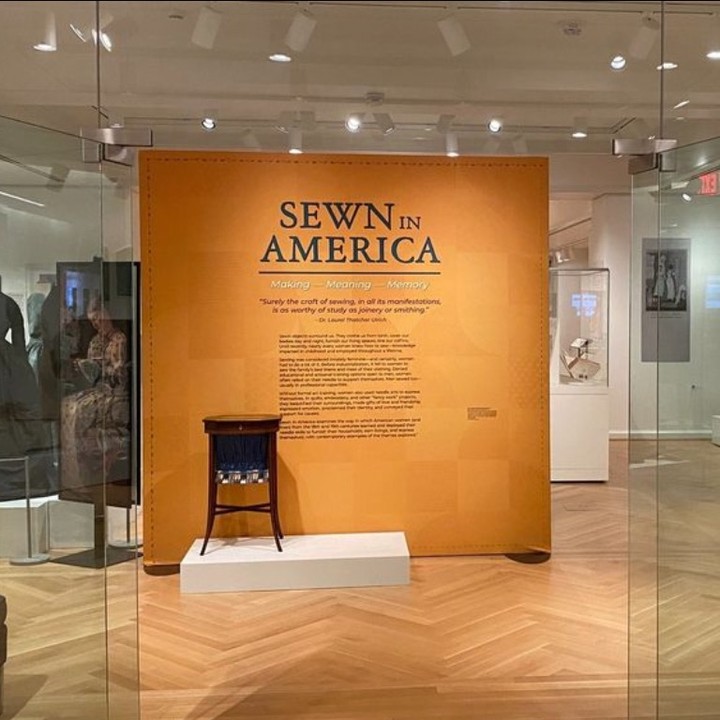

MAKING - MEANING - MEMORY: A SEWN IN AMERICA SYMPOSIUM

Part of the Special Programs collection

The DAR Museum's Symposium is based on the current exhibition of "Sewn in America: Making - Meaning - Memory. Virtual and in-person options

Date: Fri Nov 01 2024 and Sat Nov 02 2024

Time: 08:30 AM to 04:00 PM Friday, Time: 09:00 AM to 05:00 PM Saturday

Location: DAR Museum (Virtual and in-person options available)

At this symposium, we will bring together experts, artists, and enthusiasts from various fields to share their experiences, insights, and techniques. Through engaging talks, you'll gain valuable knowledge on how to create meaningful connections through art, crafts, and personal stories.

Discover the joy of making and the significance it holds in our lives. Explore the ways in which we attach meaning to our creations, and how they become a part of our memories. Whether you're an artist, a craftsperson, or simply curious about the creative process, this event is perfect for you.

Join us at the DAR Museum, where you'll find a vibrant atmosphere buzzing with ideas and inspiration. Don't miss out on this incredible opportunity to connect with like-minded individuals, expand your horizons, and leave with a renewed sense of creativity.

Mark your calendars and get ready to embark on a journey of Making - Meaning - Memory!

Virtual and in-person options available

Sewn in America Exhibition Trailer

With Their Busy Needles

On display April 26 through December 1, 2024

Samplers are more than thread stitched through cloth. As objects of art, samplers tell stories of creativity, instruction, and skilled work. As historical records, they document the lives and experiences of thousands of young women, histories that might otherwise remain unknown.

With Their Busy Needles showcases works from the sampler collection of Alexandra Peters, displayed alongside Litchfield examples from the Historical Society’s textile collection. Peters, a sampler historian and collector, serves as guest curator of the exhibit.

Know My Name: How Schoolgirls Samplers Created a Remarkable History

Sunday May 5, at 3 pm (EST)

at the Litchfield History Museum (7 South Street)

To accompany the opening of their newest exhibit, With Their Busy Needles: Samplers and the Girls Who Made Them, The Litchfield Historical Society will host guest curator, Alexandra Peters, for this lecture.

The power of the needle wielded by girls in the creation of samplers has often been overlooked in early American history. Revolutions were taking place, abolitionists were fighting slavery, and literate schoolgirls were sewing thousands of samplers that were meant to show off their accomplishments. The samplers they stitched, often strikingly beautiful, give us a surprising way to look into the lives of these girls, their families and the changing world around them.

Alexandra Peters, a collector and historian of samplers, will talk about a variety of the samplers from her collection now being exhibited at Litchfield Historical Society, how she became a collector, and why schoolgirl needleworks are so important in our understanding of women in American history.

You can register for the talk, live or on Zoom, here:

https://tinyurl.com/Alexandra-lecture

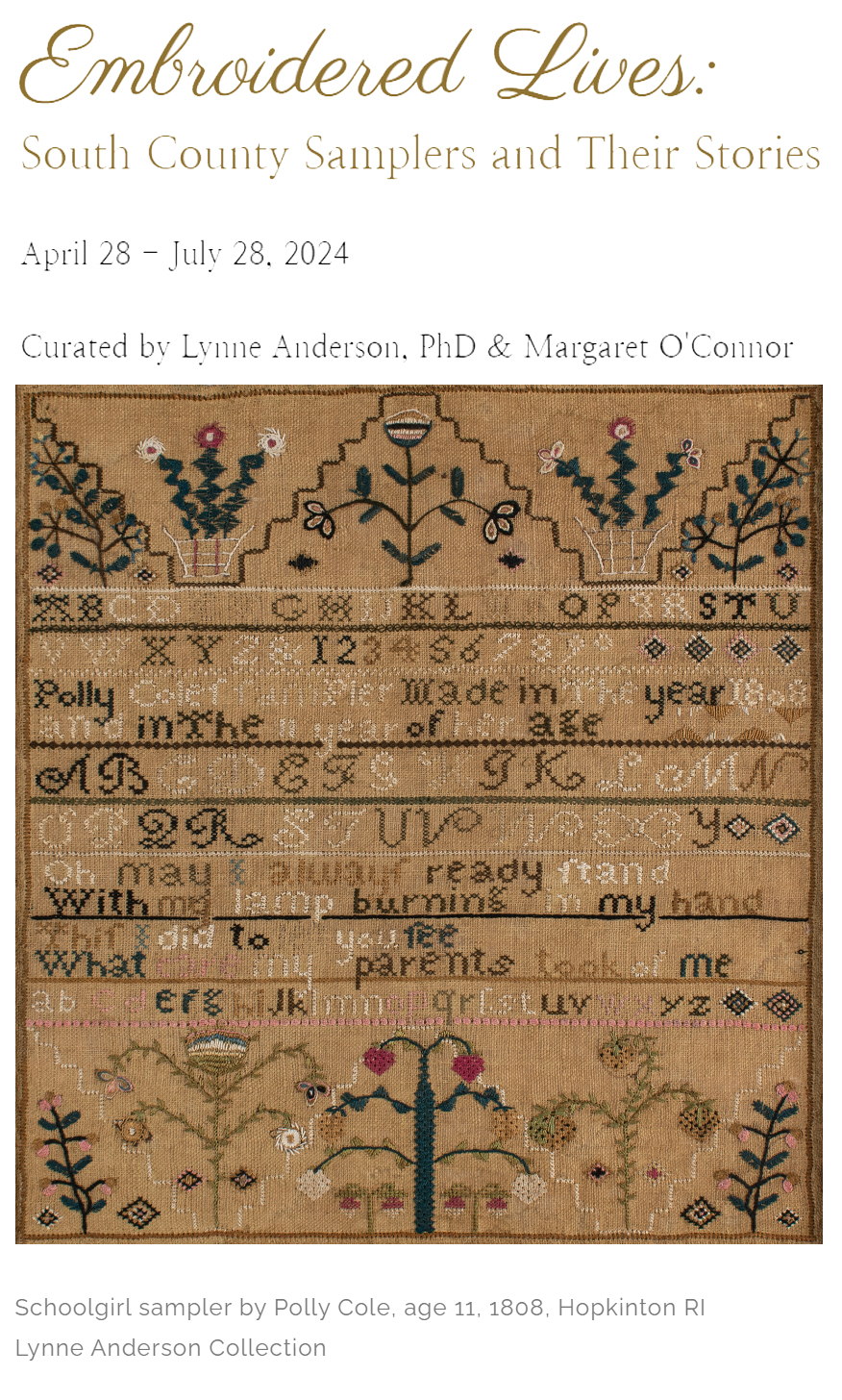

Embroidered Lives: South County Samplers and Their Stories

April 28 - July 28, 2024

Curated by Lynne Anderson, PhD & Margaret O'Connor

Until the late 19th century, needlework was an essential part of the American schoolgirl curriculum, as important as learning to read. In addition to plain sewing, most girls were taught fancy needlework stitches and used them to embroider at least one sampler – many made two or three. “Embroidered Lives” showcases 30 samplers with South County connections, exploring the social, religious, and historical contexts within which these girls lived, attended school, and stitched their samplers.

All the samplers on display are signed and most are dated, allowing us to identify the individual schoolgirls responsible for their creation. The girls represent families from all across South County and are of diverse socio-economic, ethnic, and religious backgrounds. These intricate pieces both unite these disparate experiences of girlhood and serve as material testaments to the girls’ educational and needlework achievements; testaments as beautiful and unique as their young makers.

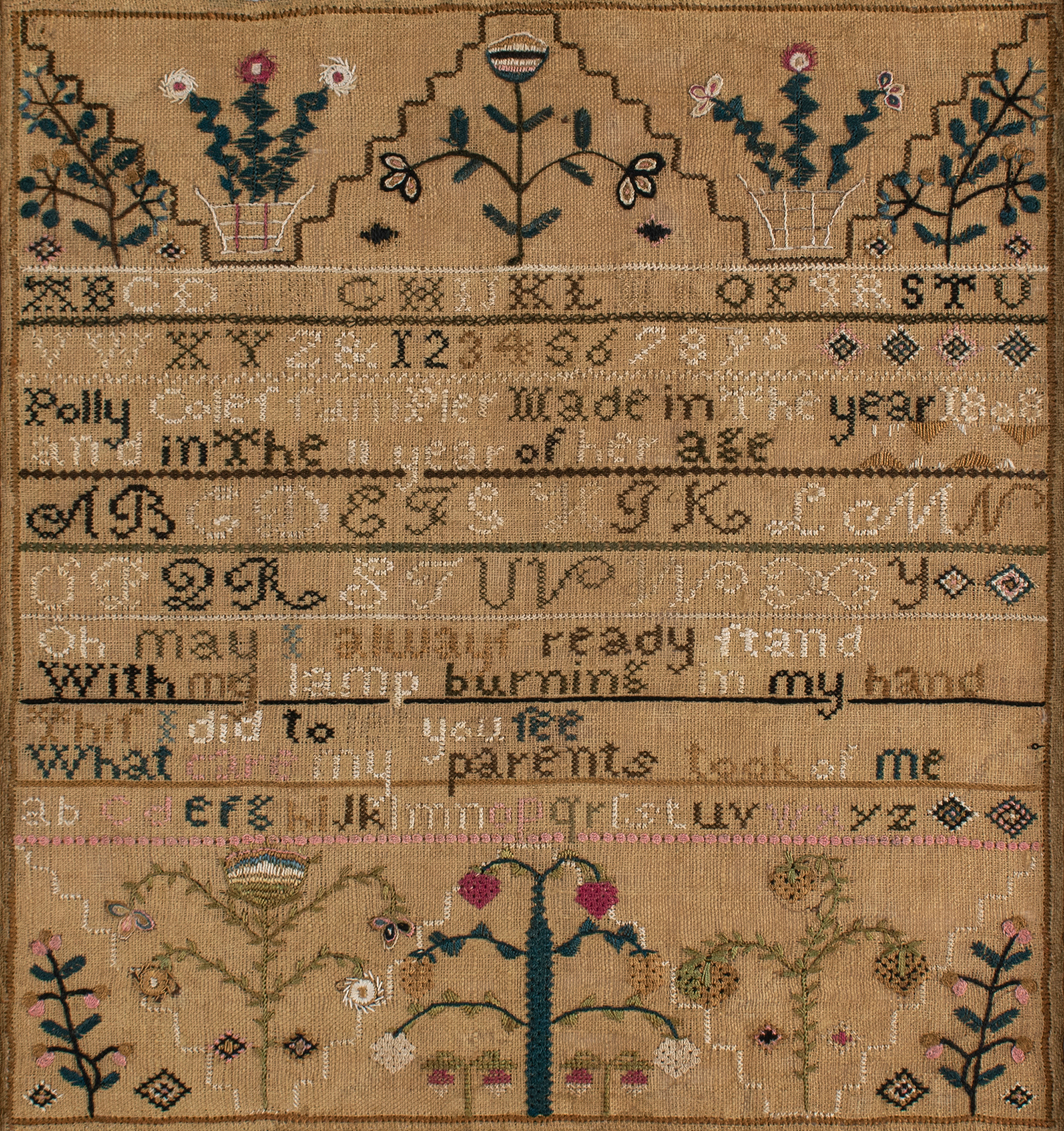

Schoolgirl simpler by Polly Cole, age 11, 1808, Hopkinton RI

Lynne Anderson Collection

Sewn in America

March 22 to December 3, 2024

Sewn objects surround us. They clothe us from birth, cover our bodies day and night, furnish our living spaces, line our coffins. For over 40,000 years humans have sewn by hand (and for a mere 180, by machine as well). Until recently, every woman and many men knew how to sew for utilitarian and often decorative purposes. Knowing a variety of techniques and stitches, and which to use for a given task, was key knowledge imparted in childhood and employed throughout a lifetime.

This groundbreaking exhibit combines sewn items from all textile sections of the DAR Museum’s collections: clothing, household textiles, quilts, and needlework. It examines the role sewing played both practically in American women’s lives, and in shaping gender roles, whether domestically or in professions from dressmaking and tailoring to factory work. Garments, quilts, and embroideries from the 18th century to today are juxtaposed to show how women of diverse backgrounds have used their needles to express emotions and identity and as a force for benevolence and justice.

Stitched in Time

Colonial Williamsburg

Opened December 3, 2022

This exhibition will be on view in the Len and Cyndy Alaimo Gallery

Needlework—which includes canvas work, lace, tambour, crewel work, silk embroidery, quilting, and counted stitch—played an important role in the homes and lives of many early Americans. Embellishing textiles with decorative stitches was one method in which the Founding Mothers contributed to their family’s household furnishings and enriched their homes and clothing with pattern, color, and beauty.

Sewing and mending everyday functional textiles such as bed and table linens, as well as clothing, was another means in which women contributed economically to their family. Stitching needlework projects was also an educational tool for young schoolgirls, and a creative outlet for many housewives.

American needlework reflects great diversity and regional variations. Many factors influenced distinct regional characteristics including the ethnic origins of the makers, trade and migration patterns, influential teachers and artists, current fashions, religious affiliations, geography, and even climate. “Stitched in Time” explores regional variations in American needlework of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and the forces that molded them.

Memorial to Terry Family by Elizabeth Terry,

Marietta, Pennsylvania, 1836.

Museum Purchase, 1962.604.1

Map of the Eastern Half of the United States by Ann E. Colson,

Pleasant Valley School, Dutchess County, New York, 1809.

Museum Purchase, The Friends of Colonial Williamsburg Collections Fund, 2019-70

Sampler by Mary Welsh,

Massachusetts, ca. 1770.

Museum Purchase, 1962-309

Link to event here