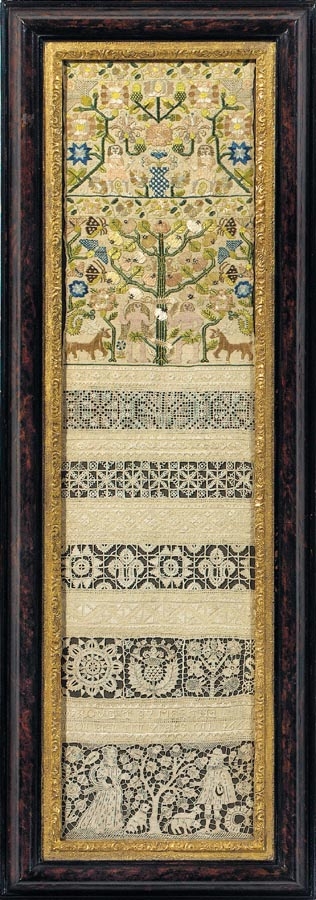

Martha Atkinson England, 1662

We turned to scholar and curator, Kathleen Staples, for an understanding and illumination of this exquisite embroidery. Excerpts from Ms. Staples’ commentary follow:

This exceptionally fine and beautifully worked example of English girlhood needlework was made by Martha Atkinson in 1662 and it exhibits features that are rare in the genre. Martha personalized her embroidery, recording in stitch that she was ten years old in 1662, the year in which she likely completed the project. She probably commenced her sampler work, however, in 1661, with the execution of the two vigorous scenes at the top of the sampler, both stitched in a colorful palette of silk threads. The usual practice, however, was to embroider, in multiple colors, a series of horizontal bands of linear, crenellated, or allover repeat patterns of architectural and floral elements. Thus, the inclusion of pictorial compositions is uncommon for girlhood samplers from this period. The scene at the top of Martha’s sampler features a complex of flowers, foliage, and nuts—all growing from a single bower-like vine. Beneath this exuberant tree-of-life arrangement are two male figures and an elegant two-handled vase, stitched to imitate a Chinese or Delft blue-and-white ceramic. The second scene is religious: Adam and Eve with the serpent and the apple tree. Although this Old Testament story was the focus of seventeenth-century pictorial compositions worked in silk and metallic threads on silk fabric, it is rare to find the subjects of Genesis, chapter three, on a sampler.1 Martha’s densely stitched version includes flowers, stags, butterflies, and caterpillars.

After completing these two sections, Martha took up the more technically challenging bands of counted thread, cutwork, and needle lace patterns, worked in gossamer-like strands of white linen thread. Whitework techniques, all of which are rooted a century earlier in the development of needle lace, require a practiced hand. As many as four distinct techniques may be found on a whitework sampler from this period: Martha’s sampler exhibits all of them. The oldest of these is counted satin stitch, which Martha used to create the dense geometric repeat patterns and her inscription. The second technique, drawn thread work, consists of removing threads from the ground fabric to form a more open weave. These remaining threads are woven together with needle and thread to form open patterns. Martha used this technique to create the openwork rose and carnation pattern at the center of her sampler.

The technique more commonly found on whitework samplers is cutwork, the precursor of true needle lace. Martha first cut away certain warp and weft threads from the ground fabric, leaving other threads to create an open square grid. This square grid served as a foundation on which she constructed variations of buttonhole stitch patterns and can be seen in Martha’s second and third openwork bands. Her patterns are adaptations of designs published in the 1500s in Germany and Italy for lace makers. Martha constructed the fourth openwork band in cutwork as well, creating a lovely starburst, which Italian designers called a rosette, a hearty thistle, and a tree-of-life stalk supporting a honeysuckle, roses, and strawberries and blossoms. Martha completed this band by working an S-scroll.

Martha’s tour de force, however, is the lowermost panel, an idyllic scene of a cavalier and his lady, accompanied by a dog and sheep, amid an oak tree and flowers. This exceptional needlework is an example of true needle lace, a form seldom found on girlhood samplers.2 In contrast to all of the techniques described above, needle lace needs no woven foundation. Instead it is constructed on a foundation of thick threads tacked down along design lines drawn on paper. After Martha completed her needle lace panel, she cut away the tacking stitches to release the paper. She then cut out of her sampler linen a large rectangular hole whose size corresponded to her needle lace panel and attached the panel to the cut edges of the linen.

Martha Atkinson’s embroidery is an uncommon find. It exhibits a liveliness and richness of design that have few equals in the genre of English seventeenth-century samplers.

Worked in silk on linen, it is in excellent condition and has been conservation mounted into a later frame.

1 For the only known published example, see Betty Ring, Girlhood Embroidery: American Samplers and Pictorial Needlework, 1650–1850, vol. 1 (New York: Alfred a. Knopf, 1993), p. 37, fig. 33.

2 Comparative examples are illustrated in Carol Humphrey, Samplers (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), p. 37, top, and p. 43; Clare Browne and Jennifer Wearden, Samplers from the Victoria and Albert Museum (London: V&A Publications, 1999), p. 49; and Anne Wanner-JeanRichard, Patterns and Motifs, trans. Vivian Blandford and Tony Häfliger (Saint Gallen: St. Gallen Textile Museum, 1996), pp. 69 and 70.