A New Discovery: The Nancy Bozyol Lane Sampler

Made at the Sarah Stivours School in Salem, Massachusetts

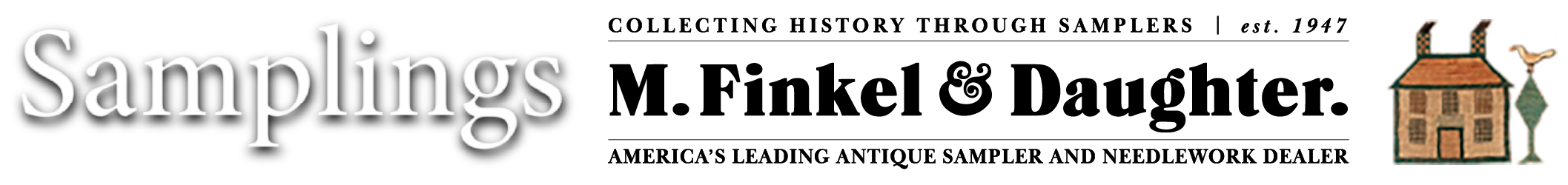

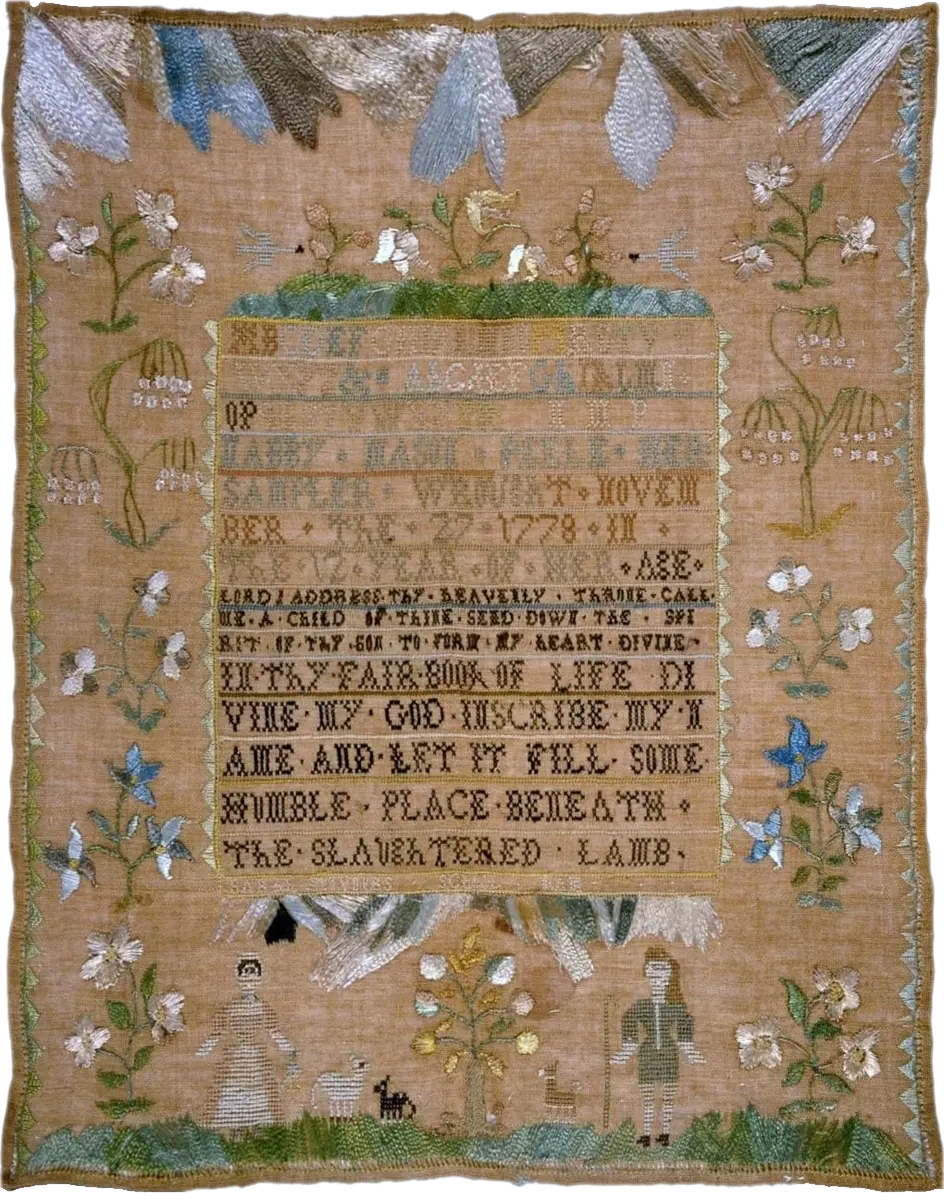

Sampler by Nancy Bozyol Lane, made at the school of

Mrs. Sarah Stivours, Salem, Massachusetts, 1784

This large and beautifully worked sampler, made in 1784 at the renowned school of Sarah Stivours in Salem, Massachusetts, has recently come to light and we are delighted to be able to offer it for sale.

More importantly, we present the following article by Mary Yacovone regarding Sarah Stivours, her school, the outstanding samplers made there and this samplermaker, Nancy Bozyol Lane (1771-1836).

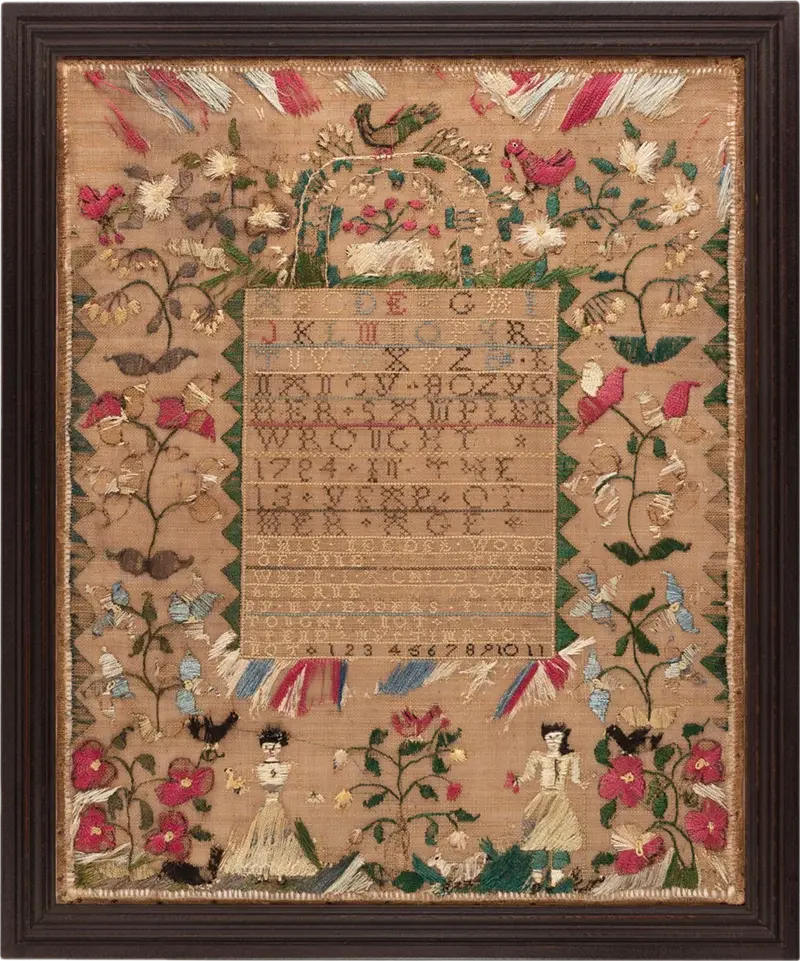

Nancy signed her work unusually, using her middle name as if a surname (the last letter of which was stitched on the line above). This was the surname of her wealthy maternal grandfather, and records show many spelling variations including Bezoil, Bazoil, Bozoil and Bezoill. It’s also possible that Nancy ran out of space and therefore didn’t include her own surname.

Detail from sampler by Nancy Bozyol Lane

Exhaustive research confirmed the samplermaker’s identity and the following article provides the result of such for the families of both Sarah Stivours and Nancy Bozyol Lane.

Worked in silk, with accents of metallic thread, on linen, the sampler is in very good condition with some loss to the silk. It has been conservation mounted and is in a molded and black painted frame with UV filter glass.

Detail from sampler by Nancy Bozyol Lane

Sampler size: 21¾” x 17½”

Framed size: 24½” x 20¼”

Now Sold

The following article is by Mary Yacovone,

Curator of Rare Books & Visual Materials, Massachusetts Historical Society

Sarah Fiske Stivours of Salem and Her School

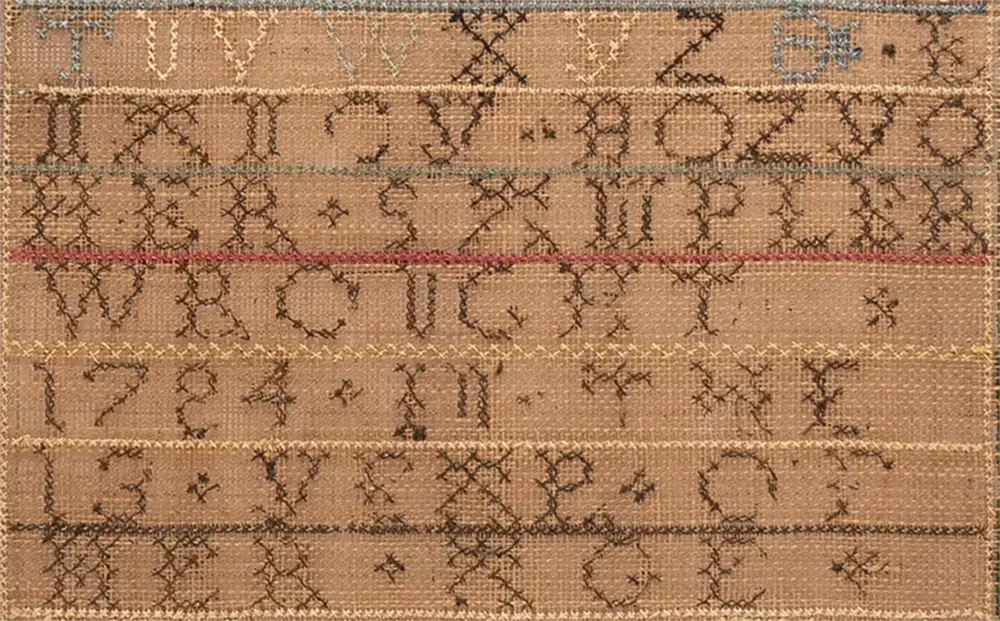

In the years between the American Revolution and the early nineteenth century, Salem, Massachusetts, experienced its heyday. A prosperous merchant and maritime class built on Salem ships plying the globe for commodities and luxury goods alike thrived in the neighborhoods close to the waterfront. Salem was truly a cosmopolitan town, exposed to people and ideas from around the world. It is in this “golden age” of Salem that a group of extraordinary and exuberant needlework samplers were worked under the tutelage of a woman named Sarah Stivours. And fortunately for historians, the lives of these Salemites were observed and recorded by the minister of the East Church, Rev. William Bentley (1759-1819), in his diary.

The Diary of William Bentley by William Bentley (1759-1819), Pastor of the East Church, 1759-1819. Salem: Essex Institute, 1905-1914

Sarah Stivours was born in 1742, the daughter of Rev. Samuel Fiske and his wife Anna Gerrish. Rev. Fiske was a graduate of Harvard College and was ordained minister of the First Church in Salem in 1718, but controversies over church authority led to his dismissal in 1735. His followers established the Third Church in Salem, over which he presided until he was again dismissed in 1745 and forced to sell much of the land he had purchased during his lifetime. Rev. Fiske died in Salem in 1770 at the age of 81, survived by his son John and daughter Sarah and at least two other siblings; his estate was insolvent. While John would go on to a successful naval career during the Revolution and a prosperous future as a merchant in the ensuing years, his sister Sarah followed a different path.

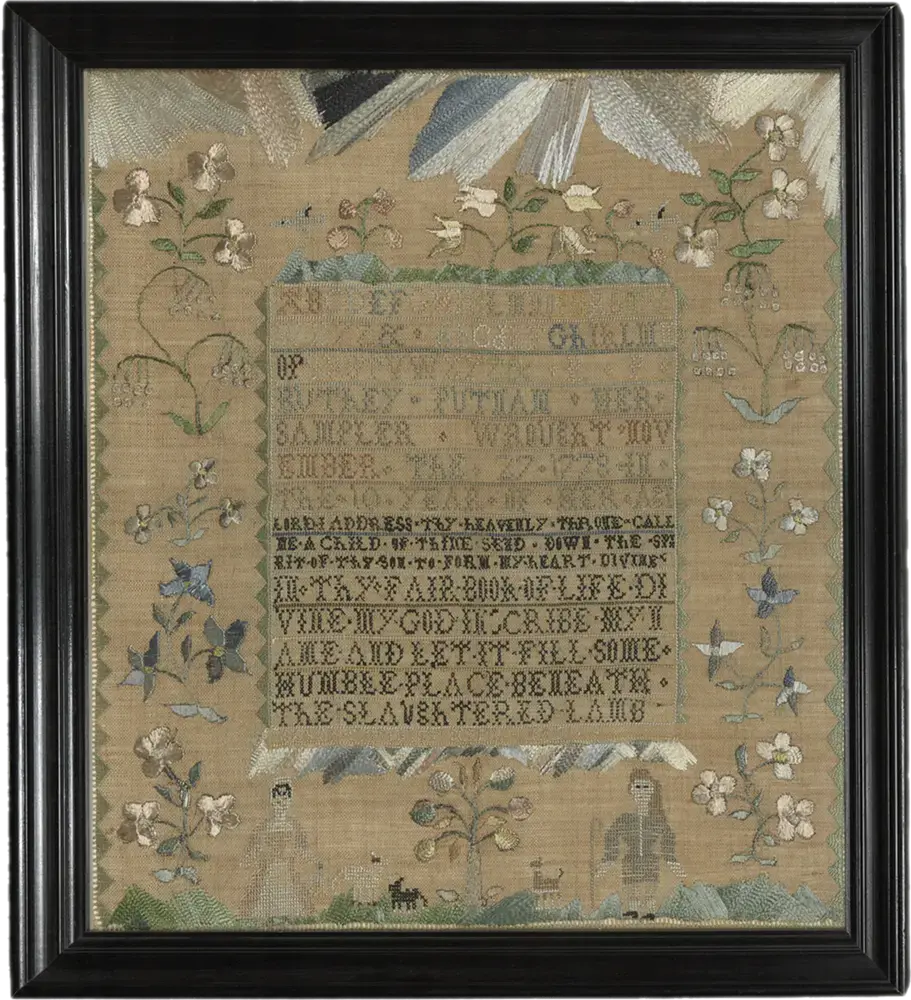

In 1772, Sarah married Jacob Stivours, a baker from Holland, whose shop was located on Essex Street opposite the pumps at Vine and Neptune Streets in Salem (current-day Charter Street, a block from the waterfront). Their marriage did not last a year—William Bentley noted only that “Her husband from a transaction in his business long since was obliged to withdraw after he had obliged her to alienate her patrimony.” One assumes from Bentley’s snarky remark that no help was forthcoming for Sarah from her brother John and in 1778, the first of the surviving samplers attributed to her school—those of Nabby Mason Peele (Peabody Essex Museum) and Ruthey Putnam (Winterthur) appear. Both feature the characteristics that would help define samplers from this school.

“At one school in Essex County, Massachusetts, taught by Sarah Stivour, the children used long stitches in this crinkly silk to represent the grass and sky. The particular use is limited to that school, and to the years between 1778 and 1786. Work from her school can be identified at a glance.”

As Ethel Stanwood Bolton and Eva Johnston Coe noted in their 1921 American Samplers, the samplers produced at Sarah Stivours’s school are quite distinctive. They identified four samplers that named the Stivours School specifically: Betsy Ives and Nabby Peele (1778), Mary Gilman Woodbridge (1779), and Sally Witt (1786), but since then, samplers that do not name Mistress Stivours have been attributed to her school, all but two worked by girls from Salem families, based on their unique style.

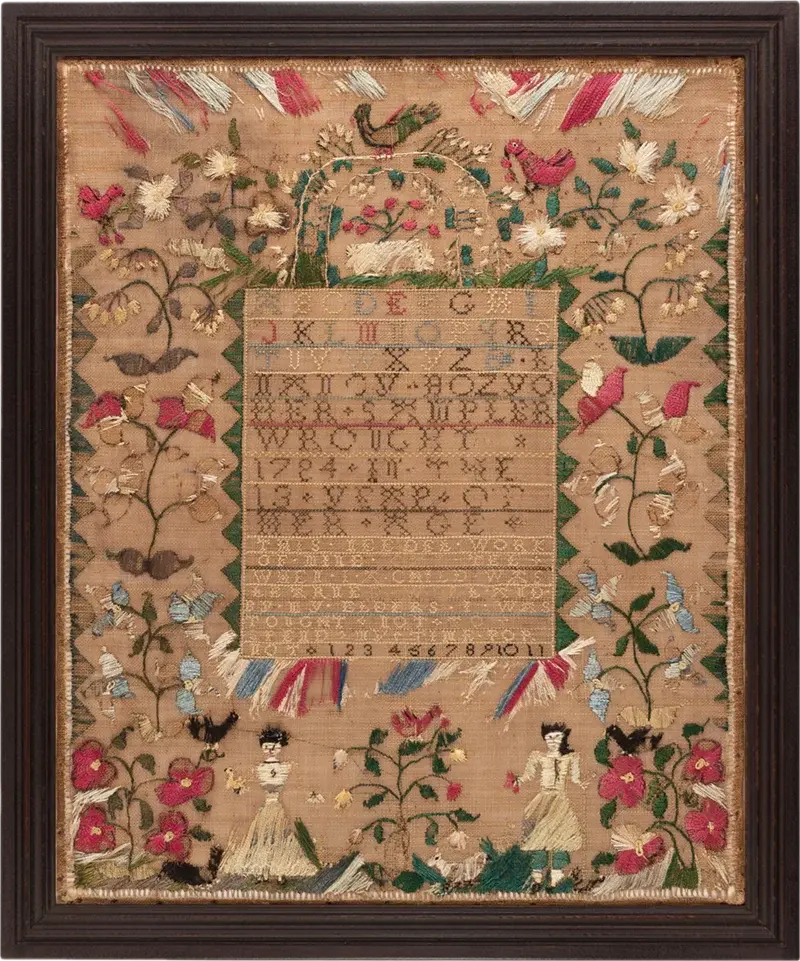

Sampler by Sally Witt, dated 1786, Provenance: Betty Ring Collection, Sotheby’s, January, 2012

Their most obvious characteristic is the use of colorful crinkly silk in long diagonal stitches gillrepresenting grass and sky, boldly calling attention to the decorative motifs in the border, an arched arbor with flowers and birds at the top and figures in a landscape at the bottom; on the sides, fanciful flowers bloom inside a sawtooth border. These long stitches would also be used by students to clothe their figures, although Peele and Putnam clothed their figures in cross stitch. The samplers also feature the formulaic signature “[name] Her Sampler Wrought [date].” In a variation on the Stivours theme, Hannah Batchelder in 1780 and Prisce Gill in 1782 populated the bottom of their samplers solely with animals and birds.

Sampler by Prisce Gill, dated 1782, “Samplers from Mistress Sarah Stivours School, Salem, Massachusetts,” by Paula Bradstreet Richter, Piecework Magazine, November/December 2000

Given the proximity of Sarah Stivours’s home to the waterfront, her students naturally included daughters of merchants, ship captains, and craftsmen living and working around Derby Street and the waterfront. Although “large” in population, Salem’s maritime community was small and close-knit and the Stivours students shared connections outside of school as well. As just one example, Sarah Stivours’s brother John married Lydia Phippen, who was the cousin of Stivours student Polly Phippen and Joseph Phippen who married student Nabby Dane. And since Mistress Stivours and the Lane family were parishioners of the East Church, presided over by William Bentley, their births, deaths, sorrows, and scandals were all duly noted in his diary.

The 1784 sampler worked by Nancy “Bozyol” Lane closely resembles the sampler worked in 1781 by Betsey Gill. Both feature long stitches worked in vibrant red, white, and blue as well as the verse “This needle work of mine can tell when I a child was learned well; by my elders I was taught not to spend my time for naught.” Betsey and Nancy populated their lower borders with figures flanking a central tree and animals. Although earlier Stivours samplers like Peele’s and Putnam’s feature verses with a more religious bent (perhaps to be expected from girls being taught by a minister’s daughter), this particular duo of Revolutionary Salem girls seems to be focused on more secular notions of learning and productiveness.

Sampler by Betsey Gill, dated 1781, Provenance: Betty Ring Collection, Collection of Sharon & Jeffrey Lipton,

photo courtesy M. Finkel & Daughter

Another pair of samplers worked in 1788 by Ruth Briggs and Hannah Byrn have also been attributed by Betty Ring to the Stivours school. These incorporate a more restrained use of blue and white long stitches for sky and clouds, and the arrangement of elements differs from the style stitched by Lane, Gill, and others.

Sarah Stivours continued to live in Salem, although it is unknown how much longer she taught school. At her death in 1819, William Bentley, her pastor for the preceding 36 years, wrote that she had “lived on the bounty of friends” and “was a woman of rude deportment & died in great obscurity.” While she may have died in obscurity, the samplers created by her students form an outstanding and enduring legacy.

Nancy Bezoil Lane and Her Family

Nancy Bezoil Lane was born in Gloucester, Massachusetts, in 1771, the first child of Nancy Bezoil and Nicholas Lane. Her mother, known as Anna, was also born in Gloucester, the daughter of William Bezoil, an Englishman, and his wife Mercy Giddings. Rev. Bentley described Anna as “one of the handsomest women of the Country” and a “most worthy mother.” Nicholas Lane descended from some of the earliest settlers of Gloucester.

Portrait of Nancy's mother, Anna “Nancy” Bezoil Lane (1751–1800) and sister, Betsy Lane (1781–1816), c. 1782. Oil on canvas, New Light: Blyth Spirits by Bettina Norton, The Magazine Antiques, June 4, 2020, Collection of Randy and Nancy Root

After serving an apprenticeship as a sailmaker with his cousin Levi Lane, Nicholas moved his young family to Salem to open his own sailmaking business around the time of the Revolution. In 1782, William Bezoil, who had returned to England, died, leaving his daughter and her children a bequest. Around this same time, Anna Lane and her sixth child, Betsy, sat for prominent Salem artist Benjamin Blyth and Nancy was stitching a sampler at Sarah Stivours’s school. It seems possible that the bequest allowed the family a few extra luxuries and may be a reason why Nancy signed her sampler “Nancy Bozyol” rather than Nancy Lane. Although Nicholas was a successful sailmaker, with such a large family, could extra money from her grandfather’s bequest have allowed Nancy to attend school and, in gratitude, honor him by signing her sampler with the name she shared with him (albeit poorly spelled)?

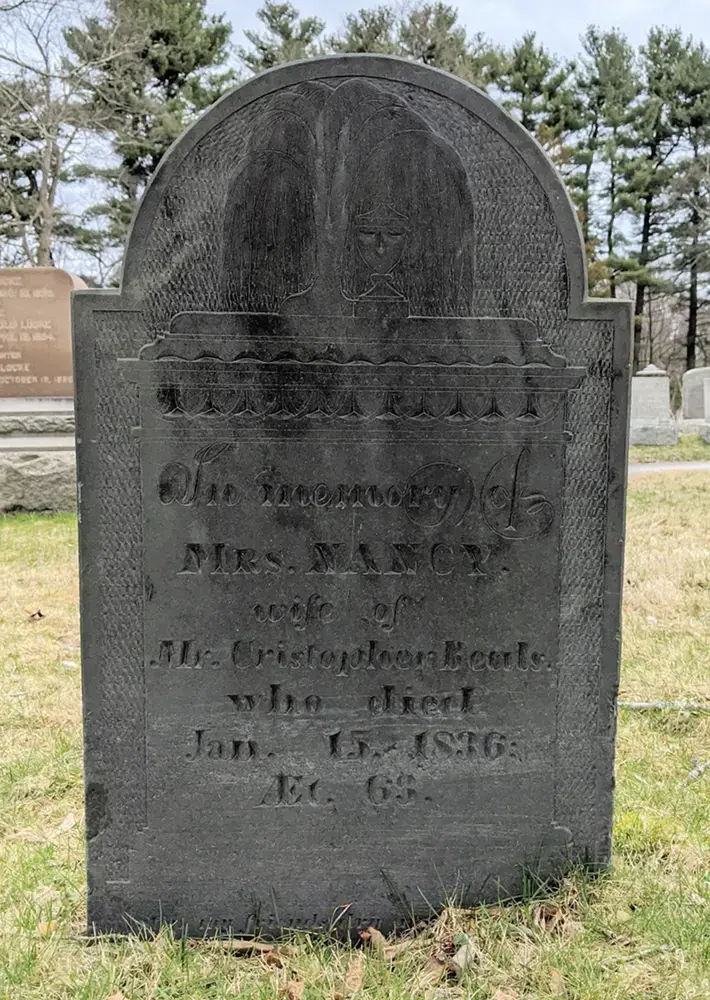

Headstone of Nancy Beals via findagrave.com

On 23 October 1791, Nancy married John Crandall, with whom she had three children. In February of 1800, John sailed for Gibraltar and was lost at sea at the age of 41. Three years later, Nancy married again to Christopher Beals, a ship joiner originally from Boston. Married for 16 years, the couple had no children together and Christopher died at the “charity house” in 1819 at the age of 55. Nancy’s life after Christopher’s death was a bit of a mystery until the discovery of her gravestone in the Munroe Cemetery in Lexington, Massachusetts, by Amy Finkel.

For someone whose entire life was spent in Salem, how and why was she buried in Lexington and why was there no record of her death in the Massachusetts Vital Records? After an early Sunday morning visit to the cemetery, all would become clear. Her daughter Eliza Crandall had married Ammi Hall of Lexington in April of 1834. Whether Nancy was living in Lexington with the couple is unclear, but her slate headstone, with a death date of 15 January 1836 and the name of her husband Christopher sits near the entrance to the historic cemetery, within feet of the memorial to Eliza and Ammi. Her death was recorded in the vital records for Salem and in the 2 February 1836 edition of the Salem Gazette, with her name incorrectly listed as Mrs. Mary Beals.

Sampler by Nancy Bozyol Lane, made at the school of

Mrs. Sarah Stivours, Salem, Massachusetts, 1784

.

Bibliography

-

Bentley, William. The Diary of William Bentley Salem: Essex Institute, 1905-1914

-

Edmonds, Mary Jaene. Samplers & Samplermakers: An American Schoolgirl Art 1700-1850 New York: Rizzoli, 1991.

-

Fitts, James Hills. Lane Genealogies, vol. 3 Exeter, N.H.: Newsletter Press, 1902

-

Norton, Bettina. “New Light: Blyth Spirits,” The Magazine Antiques, June 4, 2020 New Light: Blyth Spirits - The Magazine Antiques

-

Richter, Paula Bradstreet. Painted with Thread: The Art of American Embroidery Salem: Peabody Essex Museum, 2001.

-

----. “Samplers from Mistress Sarah Stivours School, Salem, Massachusetts,” Piecework, November/December 2000, p. 28-33.

-

Ring, Betty. American Needlework Treasures New York: E. P. Dutton, 1987

-

----. Girlhood Embroidery: American Samplers and Pictorial Needlework, 1650-1850 New York: Knopf, 1993

-

Sotheby’s (New York, N.Y.) Important American Schoolgirl Embroideries: The Landmark Collection of Betty Ring, auction catalog, 22 January 2012.

-

Swan, Susan Burrows. Plain & Fancy: American Women and Their Needlework, 1650-1850 Austin, Texas: Curious Works Press, 1995